Unlearning Part III

This contains the third and concluding segment of the conversation from the Unlearning Workshop organized by the Central New York Urban Humanities Working Group, Dec 9, 2020. Follows these links for Parts I and Part II.

Unlearning Institutions

Samia Henni: Thank you very, very much for accepting our invitation. I know that you are both facing institutional challenges at the moment and appreciate your generosity and friendship in joining us. I rejected framing this panel because that's what institutions usually do. I asked our panelists to share whatever they needed, whatever they wanted, whatever they wished to share with us.

Lesley Lokko: Much of what I'm going to be talking about tonight will come across as rather fragmented, from multiple positions, rather than a single, coherent one. I’ll be speaking in multiple voices — as a designer, design tutor, educational entrepreneur, and as an administrator. What's really important for me to state upfront, is that I don't come from an academic tradition that sees such distinctions between many of the separations that are intrinsic to the US model of architectural education; between studio and seminar, for example, or between design and research; between the profession and academia; between intuition and methodology, and between history and theory, to be honest. The absence — and perhaps poverty — of having not had a structured, “proper,” and traditional upbringing in architecture has turned out for me to be the most important, liberating tool available in thinking, designing, and implementing a de-colonizing or transformative pedagogy. I'm going to do two things this evening. The first is to share the thinking of Cameroonian philosopher, Achille Mbembe. I quote,

When we say access, we are also talking about the creation of those conditions that will allow black staff and students to say of the university: “This is my home. I am not an outsider here. I do not have to beg or apologize to be here. I belong here.”

Such a right to belong, such a rightful sense of ownership has nothing to do with charity or hospitality.

It has nothing to do the liberal notion of “tolerance.”

It has nothing to do with me having to assimilate into a culture that is not mine as a precondition of participation in the public life of the institution.

It has all to do with the ownership of the space that is a public common good.

It has to do with an expansive sense of citizenship which itself is indispensable for the project of democracy, which means nothing without a deep commitment to some idea of the public.” For Black faculty and students, this has as much to do with creating a sense of mental dispositions as it does the making of physical spaces.[1]

For Black faculty and students, this has as much to do with creating a sense of mental dispositions as it does the making of physical spaces.

We need to reconcile the logics of indictment and the logics of self-affirmation, and occupation. This requires a substantial amount of mental capital, and the development of a set of pedagogies that we could call, “pedagogies of presence.” Black faculty, staff, and students have to invent a set of creative practices that ultimately make it impossible for official structures to ignore them, to not recognize them, to pretend that they are not there, to pretend that they do not see them, or to pretend that their voices do not count.

The second thing I'm going to show is a video that was put together with my teaching partner at the Graduate School of Architecture in Johannesburg, a couple of years ago, which I slightly reworked and will be using next semester. I chose it because watching it in 2020, after both the pandemic and the protests, gave me a different reading and appreciation of it. But it also brought up the question — which for me is the only question — of curriculum. What sort of course is a “special topics” course? Is it two credits? Four credits? Is it six? What is a credit? Is it a studio? If it's not a studio, is it a seminar? What's the difference? How many contact hours will I have? What is the output? What are the learning objectives? Those questions which have to be answered ahead of time, threatened to undo its possibilities. That remains a troubling hurdle to what I call decolonizing, de-racing, and demystifying the canon.

“I once called architecture political plastic to describe the elastic way by which abstract forces—political, economic, or military—is slowing into form. We are no longer speaking about solid space. Every space is always space in movement or space under transformation. How you can start from a bit of material reality and start weaving through and moving across networks of connections and associations to the ideology that is behind. Physical structures and built environment are always elastic and responsive. Politics is the process of materialization, the drawing itself starts producing a political reality.” — Eyal Weizman

Victoria M. Young: Thank you for inviting me to be a part of this important conversation today. I'm very pleased to share my thoughts on the Society of Architectural Historians’ (SAH) work. The Society has 2300 individual and 600 institutional members around the world. We began “to unlearn” led by membership, particularly our colleagues who formed affiliate groups. These started as groups of scholars with similar interests gathering at roundtable discussions at conferences. Today, we have seven groups, including Asian American and Diasporic History, Climate Change and Architectural History, Historic Interiors, Minority Scholars, Race and Architectural History, Women in Architecture, and Architectural Studies. I'm grateful to the leaders of the affiliate groups and specifically to the Asian American and Diasporic History, Minority Scholars, and Race in Architectural History groups for their tireless work on behalf of diversity and inclusion in the SAH. They’ve pushed us to enact change and have held us accountable and challenged us to increase our work in diversity and inclusion. In order to make this happen, the SAH Board approved a standing committee for this work called SAH IDEAS. IDEAS stands for inclusion diversity, equity, accountability and sustainability. SAH IDEAS will not only create new diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, it will hold the SAH accountable by embedding the initiative into everything we do. Putting women, marginalized gender groups, the disabled, adjunct and contingent faculty, and those impacted by environmental justice and physical embodiments of racism, we feel the SAH IDEAS committee will assist us in becoming a more diverse and sustainable academic society and recommend change in our systems and policies as needed. The work of the SAH IDEAS committee will be foundational to the Society’s next strategic planning process, set to commence in June 2021.

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, the Society and its affiliate group leaders issued statements on racial and social justice. With our heritage conservation committee, the SAH leadership issued a statement on the removal of monuments to the Confederacy from public spaces, calling for the removal of the structures, something we had never done in our eighty-year history (Figure 1). We followed this with two virtual panels to discuss the monuments as objects of oppression. The heritage conservation committee has also issued statements supporting recognition of the Emmett Till house in Chicago as a landmark and opposing demolition of Buffalo’s Willert Park Courts, the first housing complex designed and constructed exclusively for African Americans in that city.

Figure 1. Layers of protest on the Robert E. Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia, July 2020. Photo courtesy of Bryan Clark Green.

In 2019 and 2020, we issued four statements and have been a signatory with other learned societies on an additional nineteen statements opposing discriminatory policies and executive orders that have a negative impact on the humanities and higher education, including plans to end visa exceptions for international students and the use of Classicism as the style for Federal architecture.

We broadened access to our conference by conducting the meeting virtually, attracting new participants. Our new virtual programming series, SAH CONNECTS, featured discussions on race and architecture and on disabilities in the built landscape, thereby taking up subjects that have been marginalized. Nearly all these events have been held free of charge or subsidized to enable broader participation. A new committee will be charged with helping us think through these events going forward. Our publications, the JSAH, SAH Archipedia, and SAHARA are actively seeking diverse content.

We've also changed the process of filling committees by advertising open calls for self-nominations. In April of 2020 the Board made reduced membership dues for graduate students, independent scholars, those with no employment, or precarious employment and retired individuals. And it added a category of membership for those who consider the affiliate groups their primary reason for joining. On Giving Tuesday of 2020, the SAH raised $5,695 which triggered a $5,000 grant to fund the SAH IDEAS research fellowships for underrepresented graduate students and emerging scholars. We plan to continue this program so people can donate through our website, just as they do to renew memberships or register for a conference. Our ultimate goal is to endow funds within the budget for this purpose.

In our 80-year history, there's only been one president who was not white, although women have been strongly represented in SAH’s leadership. Our board and officer group is slowly diversifying. Our incoming leadership of 2024 will add to this effort greatly. Our SAH staff, led by executive director Pauline Saliga, fully embrace the work necessary to support diversity, equity, and inclusion, and we vow to continue to work on redefining ourselves and the Society, in order to ensure that all voices are heard and that opportunities are open for everyone who studies the built environment.

Samia Henni: Thank you so much, Lesley and Victoria. Your presentations brought some really crucial questions to the surface. Maybe Lesley, we can start with you? You talked about mental dispossession and political reality. How do we…let’s say, reconcile? Maybe we don't have to reconcile, but because you talked about demystification, de-racing, decolonizing but at the same time, the reason to dismantle this position, how do we make these two intersect. Maybe not really reconcile, or could we reconcile these two?

Lesley Lokko: After I'd been in the US and started talking about plans for curriculum change, one phrase that kept coming into my head was a poem by Dylan Thomas: “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Somebody asked about the speed of change. Speed is a really important tool. I felt in the US, prior to the protests, that people were trying to go about change gently. They were trying to go about it in a structured, regulated, controlled, considered, generous….Essentially, in a very polite way. But actually what I think is required is radical, abrupt change. One of the reasons why it was easy to change in South Africa in 2016 actually came down to a statue. The protests in 2015 against the Cecil Rhodes statue might have seemed like protests against an object, but actually it was a protest against an entire way of thinking. When suddenly a rupture appeared, there was a freedom that I think is has been very, very hard to replicate.

The other phrase that keeps on coming to mind is that there can be no sacred cows. If you are going to enact change, you have to be prepared to sacrifice or slaughter your cows. I found that in the US, there was absolutely no appetite for slaughtering those cows. The disproportionate burden of change fell on those who stood to gain most from the change. But the resistance came from those who stood to gain the least and that was a far greater majority. The burden of trying to push change through made it almost impossible.

We said it before; the studio is different from a seminar, the methodology used here is different from the methodology used there, a credit is worth three hours of a professor’s time, in the end I found that the greater battle. Getting through all of the substratum of that kind of infrastructural, institutional, regulatory paradigms, it was like pushing away through a thicket, a forest. The thing that you wanted to change, you'd lost sight of because actually your eye had been taken completely off the ball by something that shouldn't have been there. The good work I saw was almost always in spite of the institution, not because of it. That's a terrible indictment on education. I can't say it any more politely than that.

Samia Henni: It's very polite. One of the students, I think, is asking similar questions. Victoria to you, and then we take a couple of questions from the audience. All these initiatives and all these funds and support and really being aware of the shortcomings, the potential; I think it’s brilliant. You said something about accountability and a lot of institutions are struggling with this, my own institution included: how do you make people accountable? How do we make institutions accountable? People accountable? Officers accountable? How do we make, realize, achieve this accountability?

Victoria M. Young: The important thing is that we are doing it at all those levels. So, I teach architectural history in an art history program and I chair a department, so a lot of the things I do there are important, such as working within a faculty that has more people teaching non-Western art history than Western. It’s that work we're doing as educators or architects or lovers of the built environment all the way up through an organization like the Society. Accountability is tied to that work happening on different layers of the professions. Every time we're talking about something in the Society, we think about it in the broadest way possible, and we ask for all voices. This approach is carried into our committees and when our committees are thinking about their work, they're doing the same. When people are looking at our slate of awards, nominations for awards and things like that, these principles are happening there. So, layering through the IDEAS initiative in all that we do is our goal. It's about speed too. We have so many good people connected to this organization and using their expertise to help us do things in the best way possible.

Samia Henni: Zekun Tong writes, “Is the purpose of ‘unlearning’ to step away from the existing institutions, or is it to try to bring people with different vantage points to the same table? Because there are always people with fixed vantage points (and there are many of them in architecture institutions because they are trained to be ‘tough’), and how do we engage with them in the process of ‘unlearning’?” This is a brilliant question. Lesley? Victoria?

Lesley Lokko: It's a really tough question. I've been teaching for about 30 years. And I think I've earned the right to say I'm tired. I'm really tired of persuasion. My job is not to persuade anybody. My job is to put out a process: a process that's backed by experience, that's backed by intuition, that's backed by dialogue. And to make that process available as widely, as creatively, as imaginatively as possible. What's that expression, “you can take horses to water, but you can't force them to drink”? I’m tired of asking people to drink. So I've taken my energies elsewhere. I'm no longer interested in trying to unlearn the institution. I have done that for a very long time. Now I want to make another institution.

Samia Henni: We will all be coming to you to unlearn!

Lesley Lokko: Maybe, but also learn/unlearn is a binary that is a little bit like the binary of good and bad. I'm always a little bit nervous when I hear those words because it is not de facto good…it's not de facto good to be equitable, just, etc. It's a more complex question than that. So, there's a simplicity about learning and unlearning that also makes me slightly nervous. I think those things are not binary. They're in play all the time. You unlearn as you learn, and vice versa. And for me that's more interesting. Going back to the question of the kind of regulated or structured curriculum, it negates the possibility of that kind of play. If we're engaged in a process of trying to bring in something that has systematically been excluded, we cannot bring it in under the same conditions, the same structures, the same terms by which it was excluded. A different paradigm must exist. A different kind of generosity must be in place, a different kind of ethical relationship to knowledge, to the canons of the formation of knowledge must exist, otherwise we will be here for 40 years you know. I wrote about this back in London, in November, December: the biggest opponent to change was the timetable. How can a timetable be the reason why pedagogy can’t change? Literally, I'm baffled by it.

Mabel O Wilson: I want to respond to Lesley's comment about the learning/unlearning binary because I've been thinking about that as well. When my colleagues and I drafted the statement on unlearning whiteness, it was to a very specific group of people. It was not a project of inclusivity. It was directed at colleagues who had not understood their position of power, domination, and privilege. It came out of constantly being asked…I got a questionnaire from the Architect’s Newspaper and the first question was: what tactics do you use when engaging someone who says systemic racism is something architects don't need to discuss? I thought this was a great question, but why couldn't we say: what tactics do you use engaging with someone who says white supremacy is something architects don't discuss? I literally went through all the questions and said what skills should architecture focus on to confront white supremacy in their work? For me it was being asked to tell you about my oppression, to get you to deal with why you're oppressing me, as opposed to just dealing with the problem of oppression. How do you unlearn something that is not reckoned with, which is not recognized? Unlearning for me was to say, how do you recognize that so you do differently? That was important. It wasn't about inclusivity or diversity, because inclusive to whom? Diverse from what? It skates the issue of power.

Lisa Trivedi: I'm going to jump in, just to signal that we are approaching the end of our time. I'd like to ask all of the panelists to think about next steps, and participants in the workshop, to think concretely about next steps because as a collective that might be the most fulfilling thing that we can do in the face of these challenges that we're talking about.

Victoria M. Young: I think for the Society, it's keeping on this path and moving forward. Our affiliate groups have been extraordinary. Our graduate student committee has been doing powerful work. It's a lot of things happening at once. I'm particularly excited for the work of the SAH IDEAS Committee going forward. I think that's going to change everything that we do.

Lisa Trivedi: So, what I've heard is new vocabularies, new paradigms, new ethical relationships of knowledge, new sensibilities around time and timeliness and how it impacts the way in which we think and teach and see the world. I'm going to turn to a couple of questions raised; Mabel and Swati, perhaps you'd like to respond to one of these? One is a question posed by Lisa Uddin: “Given that we are indeed talking about materiality, what are the historiographic possibilities of non-textual modes of archival reading and narrativizing? I’m thinking here of the haptic, the aural, the sense of smell, etc. I'm just wondering if there might be a particular next step that we could think about collectively that addresses that question?”

Swati Chattopadhyay: I think it's important to recognize that as good researchers, when we go out there, collect oral histories, do the ethnographic work that is necessary, that is not the solution to anything we're talking about here. That is additive. That is not regenerative. You still have to apply a practice of reading to those. It doesn't matter if it is non-textual, it's non-visual. I'm working on a project on small spaces. How do we write the history of the hidey hole? How do you write the history of that cage? How do you write that truth? What kind of language do you need to write? Where is the source? I work primarily on the historical archive and there has to be certain practices of reading. Yes, it's important to think about oral history, the non-visual. I'm thinking about sound a lot. But, I don't think we have figured out how to do that. It is extremely difficult to put that into a language of history writing. One of the struggles that I'm having is that I don't think we can write histories of that. I know I'm not writing an architectural history and I don't make apologies for that. But that's, for me, the unlearning of architectural history.

I don't teach design anymore. But as someone who has practiced as an architect before and taught studio before, I think one of the biggest problems we have about studio instruction and design instruction is that we've never really known what our real mission is. We don't teach students that the first principle is “do no harm.” We imagine architectural design is about having to build something and put it up there. No, you don't. I agree with Lesley; I don't think within our institutional systems you can actually pull that off. Yes, Charles Davis, as he described in his presentation, will be asked to teach such a studio. What is he going to do? You work within parameters. Unlearning doesn't happen within parameters. Victoria, I appreciate your position and as a fellow of the Society, I don't think we do enough. I don't think we do enough because we still stay within safe parameters, within modules we can handle, within what American institutions will allow you to handle. That is our limitation.

Lesley Lokko: It's really important that we're talking about new, new, new but actually many of the things that we're talking about have been done elsewhere. There are many schools around the world that do not subscribe to this view of education, that do not invest almost everything they have into the silo or the separation of knowledge. I was on a review where a student presented a project entirely in Zulu, which is one of the 11 official languages of South Africa. The whole panel was waiting patiently for her to translate and she said, “I'm not translating. It's not my problem that you don't speak Zulu, you have to figure out some other way to understand what I'm doing.” It was one of the most powerful presentations I've ever seen because I had to teach myself. I had to literally unlearn in order to be able to understand what she was doing. Now, those power relations certain schools allow, encourage, support that kind of work. Other schools don't. I think there is kind of parochial quality, a myopia in American schools…There are lots of places around the world that don't do this. It would benefit many schools here to see what's going on. The world is full of histories of radical schools, of schools that really change the paradigm even within the United States. This way of talking it's not universal at all.

Charles Davis II: What we're really talking about is how we create histories for architects or architectural historians so that they can benefit from the knowledge that's being produced elsewhere. People learn to do things and they do things in really interesting and innovative ways and they survive and sometimes they don't need us. They're doing what they need to be doing. The clever thing that we could be doing within our institutions is understanding what it is that they're doing and understanding when our lenses are actually preventing us from seeing and looking and interacting. When to set those lenses aside and when to subvert them because they're preventing us from seeing. Audre Lorde: “The master’s tools can never dismantle the master’s house.” We're academics in a closed space and we're trying to figure out what we need to dismantle in order to do better in this space. I think it's important for us to acknowledge our privilege and the way that we are bound in this space to improve the limits within a discipline—be it architecture, architectural history, art history, etc.—while hopefully acknowledging to ourselves, our students, our peers, and our discipline that this stuff is already happening. People of color are making interesting spaces; they are extremely creative. They're doing wonderful things. There's hundreds of years of expressive culture, material culture, that we have to learn to canonize and narrativize, and catch up with in order to change our discipline. When I have conversations, particularly with my students of color, I tell them you don't need to feel a sense of inferiority or a sense of uncanniness within this discipline. You come from a rich discipline. If this language doesn't fit you, find one that does because you're already making it. It's interesting to be within the academy to find out what those tools are, but I also have family, and I have people who work out there who are doing things, and I participate in that culture of making as well. For me, what we're talking about are the limits within our very privileged space, as opposed to the limits of production that exists out there in the world.

Ana María León: Charles, I completely agree. I make an effort to push my students outside the discipline to give them opportunities to become more familiar and be in relation with those sources. I just wanted to very quickly give a shout out to Dark Matter University, a group of BIPOC architecture faculty and students, trying to extract resources from institutions, which I think is one of the most interesting pedagogical experiments to come out of the summer. I don't want to speak for it. I'm just in support of it and have been to meetings. I would just put it forward as an example. Lisa asked for ways out. I acknowledge, Victoria, that institutions have to revise and be critical with themselves. But I also think since big institutions are sort of enmeshed in systems of capital, having counter institutions that are outside, or partially outside, those systems is a productive and necessary way to keep these discourses open.

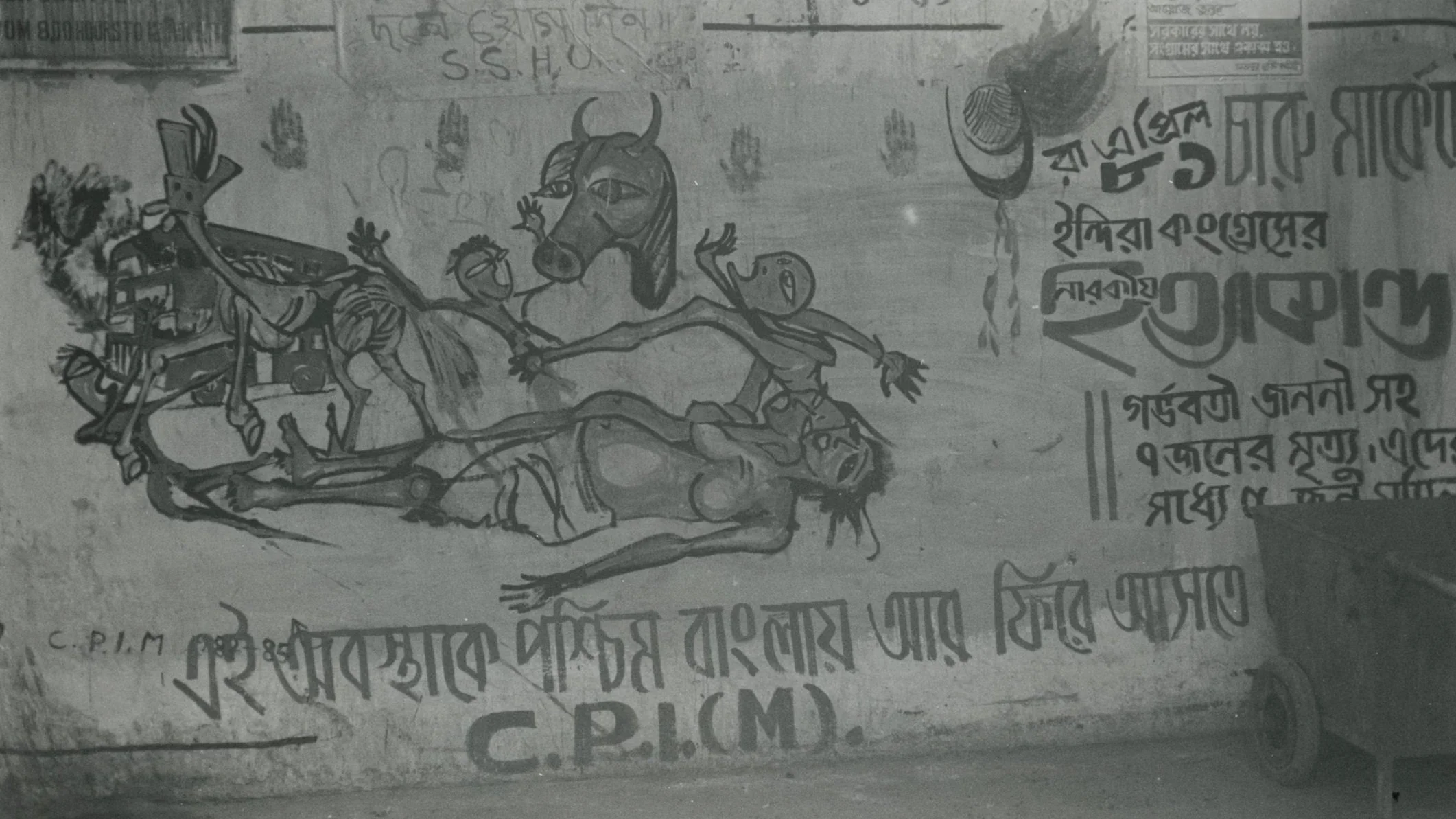

Lawrence Chua: I really appreciated Lesley and Mabel’s comments about the challenges of shifting the discourse in institutions. In the last few months, we've seen institutional calls for diversity, equity, and inclusion become a form of gaslighting. Let’s face it, they are the academic equivalent of those emails you get from corporations that claim to support Black Lives Matter. What do we do with all of these statements when, in fact, the system of racial capitalism, of imperialism, is still intact? I also appreciated Swati’s research, which has challenged us to read the landscape in a different way. It makes me think that in attending to things like political wall writing, or the kinds of spatial practices and interventions that colonized people invent to navigate the imperial built environment that Charles mentioned, pose an existential threat to the discipline as it’s taught in professional schools.

We can acknowledge that there's no need to build anything anymore. We certainly have enough buildings in the world. What is the role of the architect in an overbuilt environment? It is a question that runs counter to the goal of an institution, whose job is to produce professionals who will continue to feed the building economy. I don't mean to say that the work that we've been doing towards diversity, equity, and inclusion is unimportant. I'm just saying, it's transformed into something else. I am certainly appreciative of the radical inroads that have been made at the Society for Architectural Historians, and the efforts that it’s taken to do that. I want to acknowledge, we are all, directly or indirectly, the recipients of those initiatives.

Peter Christensen: Swati made the point that we don't tell architects, do no harm. Do no harm in 2020 might mean don't build. We have an ecological crisis that stems from habits that we need to unlearn. How can we create a system where an architect could actually have the ability to just say, “I don't want to do that project and not have it threaten their livelihood?”

Lesley Lokko: Our understanding of building is too narrow. In the same way that our understanding of professionalism is too narrow. I mean we build knowledge; we build confidence. Building is not the only thing that architects do and this kind of obsession with the profession as the epitome of competence and excellence for me is very troubling. The idea that you enter into an architecture school and the only way you can justify that training is to exit as a professional architect is problematic. Maybe it's about us reframing some of these questions because the binary of build/not build is also for me very troubling. There are different ways to build. We're all figuring our way through this, and I think it comes back to this question of speed. The speed of events outside of the academy, I think, has taken it by surprise. Everyone's reeling. The Academy has been so complacent for so long and this is a unique kind of wake-up call.

Lisa Trivedi: I was going to ask if there were final thoughts. But I think Lesley’s statement is a lot for all of us to think about, so I wanted to release all of our panelists and thank them again for such an engaged and inspiring and hopeful conversation. As Lesley said, we're all struggling in this moment, and hopefully we can use this opportunity to find a better way forward for more of us.

Notes

[1] Achille Mbembe, “Decolonizing Knowledge and the Question of the Archive.”