Strange Bedfellows: How the Pavilion of a Colonial Power came to Serve as a Beacon of the Civil Rights Movement

In 1941, the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the two African American weeklies with the highest circulation at the time, described the new Robert L. Vann Memorial Tower at Virginia Union University as “the largest memorial ever built for a Negro in America.”[1] Vann, the paper’s late editor, who had died the previous year, was an alumnus of the historically Black college in Richmond, Virginia. At 165 feet, the tower stood in proud contrast to the nearby Confederate memorials on Monument Avenue that had been erected beginning in 1890. Vann’s widow Jessie, who succeeded him at the paper’s helm, pledged $25,000 towards the tower, undoubtedly in part as a riposte to those statues (which stood until they were pulled down in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020). At the time it was not easy for African Americans to challenge Jim Crow. The tower conveyed its message through its name and height rather than more overt symbols like figural statuary or classical embellishment. In part as a consequence it has largely been forgotten. It deserves to be remembered, and not only as the rare monument to Black achievement in the United States but as a pioneering example of modern architecture in America.

Figure 1. Postcard of Belgian Pavilion, World’s Fair, Victor Bourgeois, Léon Stynen, and Henry van de Velde, New York, 1939. Source: Boston Public Library Print Department.

One of the earliest examples of European modernism to be erected on a U.S. campus, the Vann Memorial Tower and the Belgian Friendship Building of which it is a part were designed by a trio of distinguished modern Belgian architects — Victor Bourgeois, Léon Stynen, and Henry van de Velde — although not for Virginia Union, or in Richmond. It was built, rather, as Belgium’s contribution to the 1939 World’s Fair in Queens, New York. A showcase for Belgian craftsmanship, design, and materials, it included tiles from the region of Courtrai, schist facing from the Ardennes, and diamonds and other products from the Belgian Congo, the country’s largest and oldest colony.

That the pavilion ended up at an institution of higher education for Black people — a people whose violent exploitation in the Congo was a notable feature of both the building and of modern architecture in Belgium more broadly — is just one of the many ironies of the Belgian Friendship Building. Its story, which we explore further in a new book, makes clear how far a building’s use can stray from the one intended by its original client and designers.

““Vann Memorial Tower and the Belgian Friendship Building remain proud . . . rejoinders to Richmond’s White monument culture.””

The Belgian pavilion’s improbable journey unfolded in spring 1940, after Germany’s invasion of Belgium. That May, the Belgian government in exile presided over the disposition of the building as a “gift” to Virginia Union on the condition that the college pay for the disassembly, transportation, and re-erection of its Belgian-made parts (costs that ultimately exceeded those of an entirely new building).

Belgium’s motivation lay at the intersection of race, colonialism, and the burgeoning global war. Its regime in the Congo had long been among the most brutal and infamous. African Americans, leery of going to war to support European imperial powers, knew this. Black journalists were especially skeptical of Belgium’s claims to have reformed the murderous practices introduced by Leopold II earlier in the century. As the Courier wrote in June 1940, “Before shedding too many tears over the plight of Belgium, Negroes in America should consider that Mississippi is heaven for colored folks compared to the Belgian Congo.”[2]

Figure 2. “Virginia Union Moves Forward” from the VUU’s Annual Bulletin, 1941. Source: Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

The scheme to move the Belgian Friendship Building to Richmond involved an unlikely cast. The idea originated with Jan-Albert Goris, a prize-winning Flemish atheist writer and deputy commissioner of the Belgian pavilion whose job included not just building the pavilion but disposing of it — at someone else’s expense. That meant finding homes for its displays and someone willing to remove the structure from the fairgrounds. At some point, he alighted on the idea of giving of the building to Virginia Union, whose treasurer, a White man named Sydney Hening, saw the internationally acclaimed design, with its steel frame, large expanses of glass, and warmly textured hand-molded tile and schist facing, as a prestigious way to modernize his campus. The project also enjoyed the support (despite some well-justified doubts) of John Malcus Ellison, an alumnus of Virginia Union who, in 1941, became its first African American president.

Rockefeller philanthropy played a role in brokering the deal. Virginia Union consisted of two seminaries that had been established by the American Baptist Home Missionary Society in 1865 and amalgamated in 1899, but by 1940 was partly underwritten by the Rockefeller-funded General Education Board. The Rockefellers were friendly with Belgium, having supported the country during World War I. The GEB’s enthusiasm for the new pavilion project attracted an endorsement by first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and, more important, a who’s who of African American supporters to an unprecedented, national fundraising campaign that culminated in the naming of the tower for Robert L. Vann. Although U.S. entry into the war triggered a pause in fundraising, it also provided a new source of support: Virginia Union rented out the hall as an induction center, serving African American and White soldiers on alternate days (the U.S. military was not desegrated until 1948).

Work on the reconstruction, meanwhile, was put on hold. War-time shortages of labor and materials was one reason. Another was that Belgian architect Hugo van Kuyck, who along with the African American architect Charles Russell was charged with overseeing the rebuilding, was preoccupied with his commitments to the Belgian government in exile (he later joined the U.S. Army, which kept him busy plotting the Allies’ D-Day landing on the Normandy beaches). The building was rededicated in 1949, celebrated as a beacon of freedom, democracy, and interracial partnership.

In the move from fairground to campus, the Belgian Friendship Building was subtly transformed. Van Kuyck re-organized what had originally been a courtyard-oriented scheme designed to resemble a Belgian town square into a U-shape facing North Lombardy Street, which connected the campus to the Black neighborhood of Jackson Ward. In terms of program, it came to house a range of facilities, including a library, science laboratories, and a gymnasium. Of equal importance, the building’s dehistoricized language became a symbol of African Americans’ upward social mobility and empowerment. Virginia Union featured it in publicity brochures even more than its distinguished Romanesque buildings. And it became the hallmark of a generation of graduates, many of whom assumed leading roles in the local Civil Rights movement. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke in the building five times between 1956 and 1963.

Figure 3. Congo bas relief by Arthur Dupagne, Belgian Friendship Building, 1939. Photograph by Katherine M. Kuenzli, 2022.

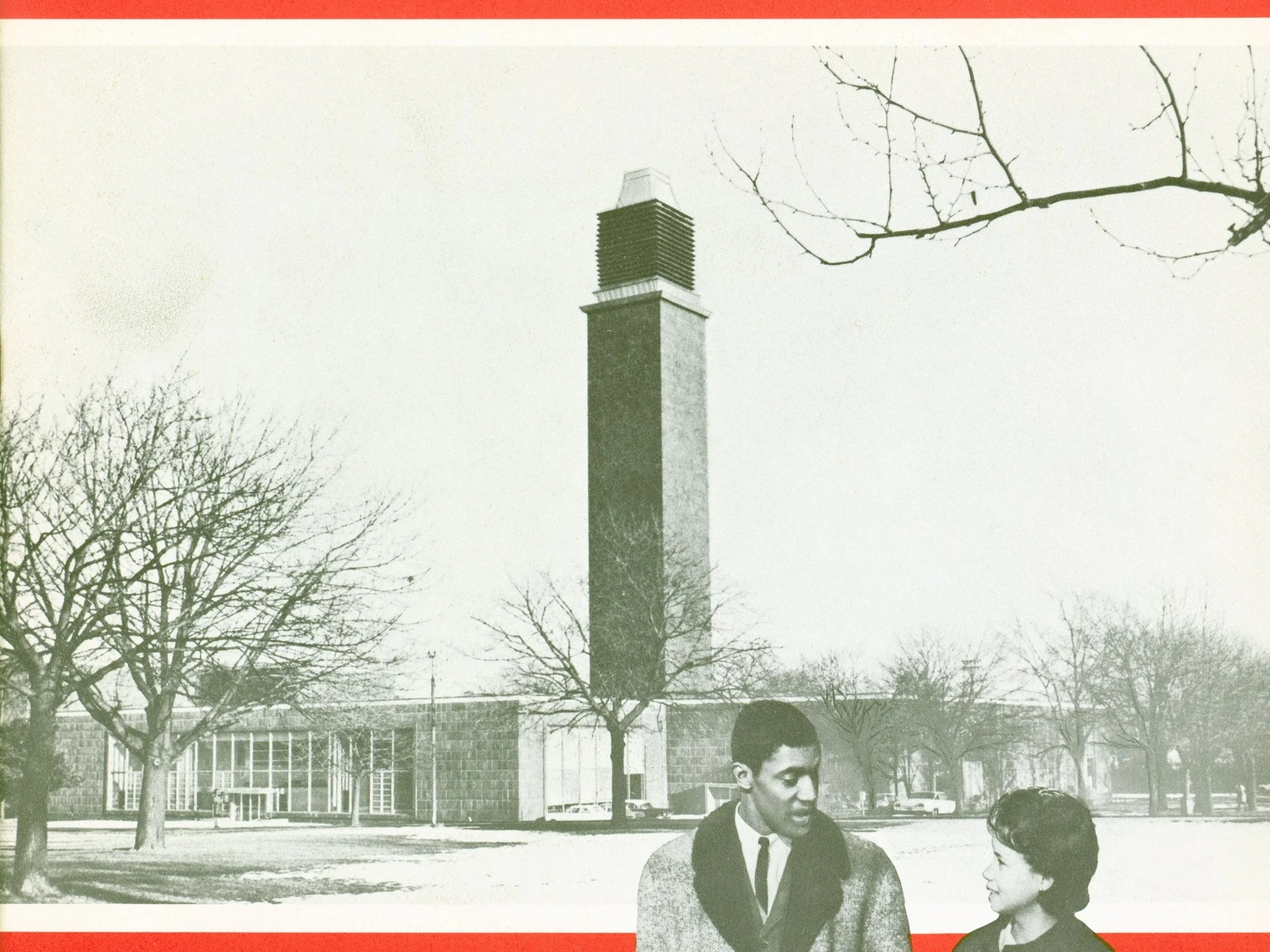

Figure 4. “For Our New Day,” from a VUU in-house publication, 1965. Source: Virginia Union University Archives and Special Collections.

And yet the building’s new identity never fully masked its old one. Bas reliefs extolling Belgium’s purported “civilizing” mission in the Congo are still visible. So are tensions that animated the project from the start, including financial. Virginia Union has a negligible endowment (today only $32 million). Goris mispresented the Belgian Friendship Building as “permanent” when it was never meant to last. Rebuilt using a system suitable only for temporary structures, its tile cladding was reattached to the steel frame without a waterproof layer, and heavy rains have since caused heavy damage. A well-meaning recladding of the tower in the winter of 1971-72 sponsored by Reynolds Aluminum (a local company) removed both the original tiles and the glazed corner that Lewis Mumford hailed as a “a dramatic point of emphasis” when illuminated from within at night.[3] That it was made entirely of imported materials with metric sizing compounded the difficulty of maintaining it.

Still, Vann Memorial Tower and the Belgian Friendship Building remain proudly emblematic of the aspirations of mid-century African Americans for educational excellence and political empowerment — and powerful rejoinders to Richmond’s White monument culture and to histories of modern architecture that rarely venture to the American South.

Citation

Kathleen James-Chakraborty, Katherine M. Kuenzli, and Bryan Clark Green, “Strange Bedfellows: How the Pavilion of a Colonial Power came to Serve as a Beacon of the Civil Rights Movement,” PLATFORM, Feb. 9, 2026.

Notes

[1] “Laying Cornerstone at Va. Union University for Belgian Building,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 21, 1941, 18.

[2] Samuel L. Brooke, “The World This Week,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 1, 1940, 4.

[3] Lewis Mumford, “The Sky Line in Flushing,” New Yorker, June 17, 1939, 45.