See You at the Lesbian Tent: Architecture and Politics of Transnational Lesbian Activism

In March 2025, Outright International—an LGBTIQ human rights non-governmental organization (formerly the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, IGLHRC)—posted a set of visuals on Instagram reading “See You at the Lesbian* Tent” (Figure 1).[1] The posts marked the thirtieth anniversary of the lesbian campaign at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women (FWCW) held in Beijing in 1995, where the “now-iconic” lesbian tent stood.

Figure 1. “See You at the Lesbian* Tent,” posted by Outright International on Instagram, March 13, 2025. Visual by Hazel Olson-Dorf for Outright International.

A white canvas shelter temporarily erected at the FWCW’s parallel NGO Forum in Huairou, Beijing, the tent served as the designated space for international lesbian organizations and delegates, many of them longtime activists for lesbian rights (Figure 2). Over ten days, they made the tent a home. Amid overt surveillance and hostility from the Chinese state, they organized workshops on health, youth, human rights, and regional organizing across Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and the global South. It was also a place where lesbians networked, distributed pamphlets, held strategy sessions, screened movies, staged performances, and partied.

Figure 2. Exterior view of the lesbian tent, NGO Forum of the U.N. Fourth World Conference on Women, Huairou (Beijing), 1995. Courtesy of Outright International.

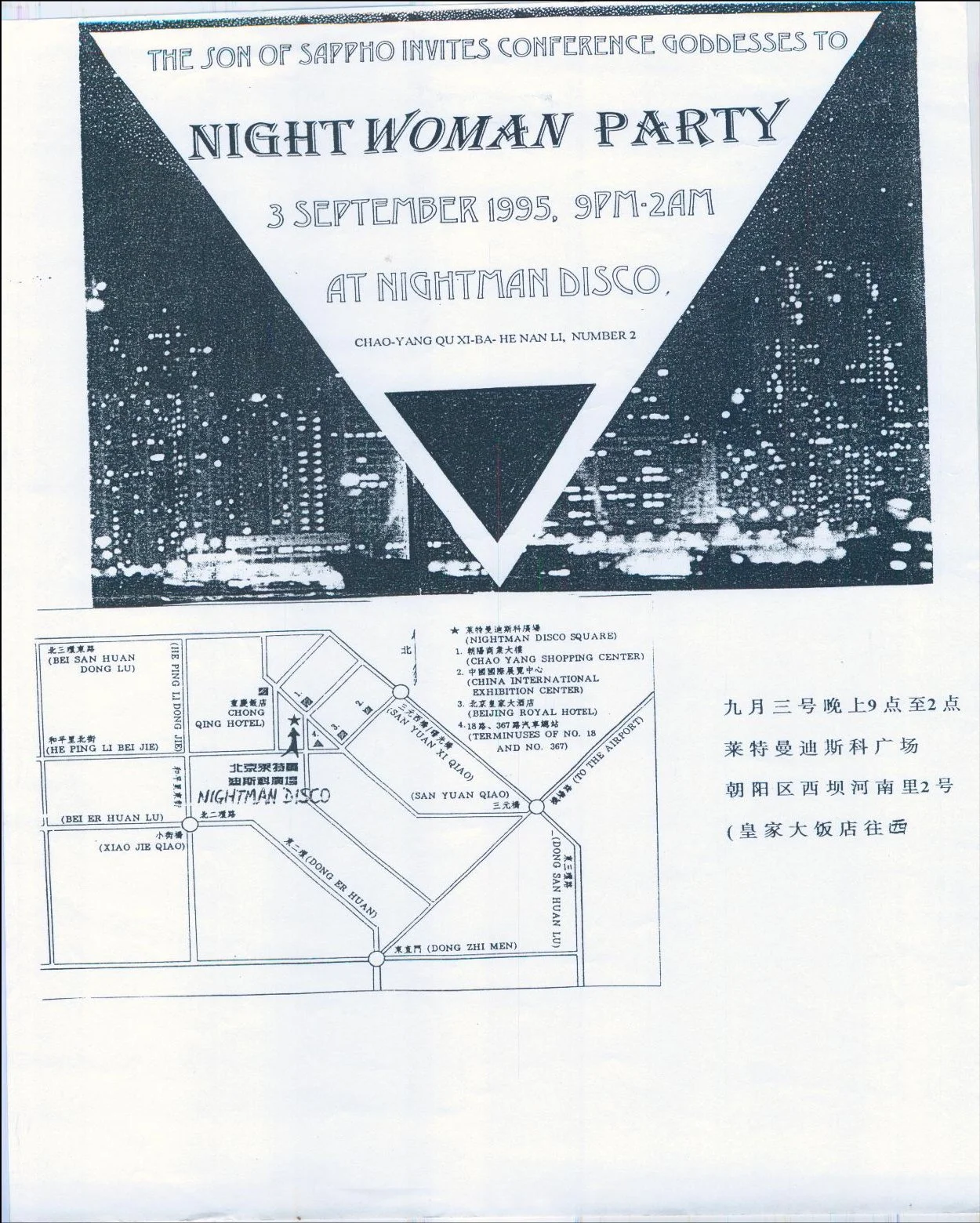

The energy of the tent spilled outward, taking form in a demonstration at the official conference, a march through the Forum campus (Figure 3), and, briefly, in a “Night Woman Party” organized by local gay activist Wu Chunsheng at the Nightman Disco in central Beijing. While Chinese lesbians were largely blocked from the tent or the conference in general, they joined the foreign delegates at this party, even under the watch of heavily armed military. In Norwegian activist Gro Lindstad’s recollection, the Night Woman Party was portrayed as an extension of the lesbian tent, bringing together a community that was otherwise scattered across shifting moments of presence.

Figure 3. Lesbian march at the NGO Forum, Huairou (Beijing), September 1995. Courtesy of Outright International.

Thirty years later, lesbians who attended the conference still fondly remember the tent as “beautiful,” “remarkable,” and “a safe space of our own.” Outright’s commemoration echoes a long-established narrative around the tent following the Beijing conference, one that casts the architectural object as a symbol of lesbian solidarity and radical visibility.

Yet, as an architectural historian studying the interplay between queer spatiality and China’s postsocialist governance, I see problems with the neat symbolism assigned to the lesbian tent. The contradiction I struggle with is this: if the Chinese government was an inhospitable host, what does it mean that it was also, in crucial ways, the “architect” of the tent? Why did the state tolerate a march where delegates chanted “lesbian rights are human rights,” yet arrest and expel Wu Chunsheng for organizing a disco party? Perhaps “radical visibility” is insufficient to capture the tent’s layered meanings, as it stood at the intersection of transnational lesbian-feminist organizing and China’s neoliberal reforms—and, I argue, functioned as infrastructure for both. This article recasts the lesbian tent in that dual light.

Building on two decades of transnational organizing—beginning with the first World Conference on Women in Mexico City in 1975 and continuing through Copenhagen (1980) and Nairobi (1985)—the FWCW itself was a milestone in global lesbian activism. There in Beijing, South African activist Beverley Ditsie became the first openly lesbian woman to address the U.N., calling for the recognition “that every woman has the right to determine her sexuality free of discrimination and oppression.” Activists pressed to include the phrase “sexual orientation” in the projected Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Although the term was excluded from the final document, the lobbying efforts catalyzed global debate and coordination around lesbian rights. In Lesbians Free Everyone, a documentary Ditsie directed, produced, and wrote at the conference’s twenty-fifth anniversary, she described the actions in Beijing as “the biggest lesbian visibility campaign in history.”

To acquire “a space of our own” was part of the fight in this trajectory. In Mexico City, lesbian presence was limited to a handful of impromptu workshops. By Nairobi, alongside official workshops, activists had claimed a fixed spot on the lawn which functioned as an information hub, and a borrowed table briefly turned it into a “lesbian stand.” In the lead-up to 1995, Thai activist Anjana Tang Suvarnananda first pressed Forum organizers for a designated lesbian space. Others quickly joined the call, and when a space was promised, IGLHRC took the lead in coordinating logistics and preparations. For the first time since the inaugural World Conference on Women, lesbian delegates were offered a shelter—or, in Ditsie’s words, a “home for ten days.” Born of transnational collaboration, the lesbian tent in turn enabled more conversations, partnerships, hugs, tears, and laughter.

If the fight for a lesbian space at the U.N. conference took place before and outside of Beijing, the physical object of the tent seems to have materialized the symbolism in Huairou. An architectural profile of the lesbian tent—registering both material scarcity and creative use—can be sketched by translating activists’ accounts into architectural terms. Set atop a concrete platform roughly matching the tent’s canopy in size, the structure was supported by slender columns placed around the edge, creating an open, wall-less space that connected freely with neighboring NGO tents. Inside, movable chairs were arranged and rearranged to suit each gathering—workshops, press briefings, parties—making room for spontaneous, non-hierarchical configurations. Textile crafts, protest banners, printed or hand-painted posters hung from the tent’s frame, transforming the space into a site of collective authorship. Together, these spatial gestures produced an aesthetic of grassroots resistance—improvised, decentered, and defiantly visible (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Beverley Ditsie speaking in the lesbian tent, Huairou (Beijing), 1995. Photograph by Rachel Rosenbloom.

Yet such a profile overlooks the Chinese state’s role in the production of the tent and casts activists as its sole creator. In that reading, the tent is slotted back into a linear genealogy of lesbian campaigns at U.N. conferences—moving from Mexico City to Nairobi and “from a table to a tent”—while being detached from the sociopolitical and urban contexts of 1995 Beijing.

To resituate it in Beijing: the lesbian tent was one of eighty-six tents—and among them, one of seven “diversity tents”—at the NGO Forum in Huairou, a rural county thirty miles north of central Beijing where the official intergovernmental conference was held. The distance was unusual: when China was selected in 1992 to host the projected FWCW, the U.N. had emphasized “the importance of close proximity between the forum and the Fourth World Conference on Women.” More consequential, indeed scandalous, was the Forum’s last-minute relocation from the Workers’ Sports Complex in central Beijing to Huairou less than five months before the event. The Chinese government framed the move as a response to structural flaws discovered at the Workers’ Gymnasium, an explanation many delegates found less persuasive than pretextual. As Liu Bohong, then associate director of the NGO Forum’s organizing department, later confirmed, the relocation was in fact prompted by party officials’ belated realization, after attending the NGO Forum at the World Summit for Social Development in Copenhagen in March 1995, that NGO politics often occupied the progressive edge of liberal-democratic discourse and could involve disruptive expressions such as demonstrations, protests, and marches.

The authorities’ strong reaction likely owed in part to still-fresh collective memories of protest in Beijing, particularly those tied to the Workers’ Sports Complex. The complex comprised two major structures: the Workers’ Stadium and the Workers’ Gymnasium. Completed in 1959 and 1961 respectively, around the tenth anniversary of the founding of the “New China,” these buildings formed part of the state’s repertoire for projecting national image through highly politicized sporting events. Yet their function and symbolism extended well beyond sports. In the 1960s, the Workers’ Stadium hosted mass rallies denouncing “American imperialism” and “Soviet revisionism,” as well as large-scale political assemblies during the Cultural Revolution. After the launch of the Reform and Opening-up policy in 1978, the country shifted away from far-left mobilization and a stagnant command economy toward marketization and controlled ideological liberalization. The 1980s saw growing contradictions within this postsocialist transformation, culminating in the 1989 student protests demanding democracy, liberty, and free speech. Although ideologically opposed to the Cultural Revolution, the 1989 demonstrations invoked overlapping spatial scripts—not only with Tiananmen Square as the protest stage, but also with the Workers’ Gymnasium as a symbolic conduit, linked by the protest anthem, Cui Jian’s “Nothing to My Name,” first performed there in 1986.

The post-1989 reform project, consolidated by Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992, decisively distanced itself from any radical agenda of political reform, whether communist or democratic. Instead, it firmly focused on economic development, for which stability—in both domestic and international arenas—was considered essential infrastructure. It was in this context that, in 1991, China appealed to the United Nations to host the projected FWCW, treating the event as an opportunity to repair its global image and lift Western sanctions in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. As then Foreign Minister Qian Qichen put it, the goal was “to create a favorable international environment for the Reform and Opening-up.”

Hosting the FWCW was thus strategically positioned to stabilize China’s international standing in service of economic growth. Yet within the event itself, the NGO Forum carried the potential to tip the balance: if staged in central Beijing at the Workers’ Sports Complex, where memories of mass mobilization lingered, it risked unsettling the domestic front the government was equally determined to keep stable. The Forum’s last-minute relocation was driven by the imperative to maintain this dual stability. A thirty-mile separation functioned as an apparatus of managed visibility: it allowed an international cohort led by feminist activists and grassroots organizers to convene in Beijing while preventing their voices from reaching domestic audiences. Coupled with limited public and private transportation, media control, and tightened surveillance of local residents during the conference, the move effectively contained what officials deemed an unstable “Western” element that was the NGO Forum within the segregated spaces of Huairou.

“Designed to preserve the dual stability, the tent simultaneously enabled and contained lesbian visibility within China.”

One of the most widely circulated anecdotes of the conference reveals that the state’s desired stability was, among other things, a heteronormative order. Documented in numerous participants’ accounts, a rumor spread before the event that lesbian activists planned to march topless through the streets of Beijing. However absurd the story, the factual part is that local authorities took it seriously enough to prepare bed sheets to cover any “naked protesters.”

When the story was retold in Lesbians Free Everyone twenty-five years later, Serbian activist Lepa Mladjenovic is captured quipping, “All 40,000 women from all around the world had to be moved because of lesbians.” Likely intended as sarcastic hyperbole, the line nonetheless compresses a complex decision into a single cause, thereby reproducing a familiar binary in activists’ accounts: state versus lesbians, fear and violence versus defiance. That same frame underwrites the lesbian tent’s symbolic power: cast against erasure through relocation, the tent emerges as an object of radical visibility.

Yet this binary portrayal risks flattening the more complex interplay between China’s postsocialist governance and transnational lesbian activism. Rather than standing against relocation, I argue that the lesbian tent equally operated as part of the state’s spatial strategy. Designed to preserve the dual stability, the tent simultaneously enabled and contained lesbian visibility within China.

When the relocation was announced, Huairou—despite upbeat official publicity—was far from equipped to host a world conference. It lacked adequate accommodations, meeting venues, transport and communications infrastructure, and even a single hall large enough for daily plenaries. With only five months left, the government launched an emergency building campaign; by the Forum’s opening, facilities only barely met basic requirements. A shuttle bus service was set up, though it proved notoriously unreliable. Accommodation included not only hotels but also refurbished private apartments. The Forum campus ultimately occupied a 42-hectare site on the western end of Huairou’s main avenue, with a dispersed assemblage of high school buildings, hotels, training centers, and tents. Among them stood an unfinished concrete shell, the “Willows,” pressed into service for exhibitions as well as a “freetime bar” (Figure 5). Much of the ground was unsurfaced. Narrow flagstone paths, some as little as half a meter wide, stitched together tents, conference rooms, and event areas. Persistent rain during the Forum’s first half strained these already modest conditions, turning the site into a swamp of mud and puddles.

Figure 5. “The Willows,” an unfinished concrete shell at the NGO Forum, Huairou (Beijing), 1995. Photograph by Katherine Steichen Rosing.

Although these conditions imposed significant inconvenience on delegates, the facilities did sustain the Forum’s basic program, a fact crucial to the state’s aim of creating a more favorable international climate by hosting the event. With no time to construct enough permanent buildings, temporary tent structures—despite being non-standard in design, structurally fragile, and at times resembling oversized inflatable bouncy houses—became essential to the operation of the relocated Forum. In other words, tents made possible not only the historic women’s conference and the “biggest lesbian visibility campaign in history,” but also the Chinese state’s agenda: to achieve contained visibility rather than complete erasure. Thirty years later, having banked the cultural capital of hosting the FWCW, the state continues to claim that “Global women's cause will sail again from Beijing.”

In contrast to the Forum’s modest material conditions, its official representation told a different story. Huairou’s building campaign enacted a familiar script in the People’s Republic of China: that of the spectacle of accomplishing daunting construction tasks in impossibly short timeframes. From the “Ten Great Buildings” of 1959 to the Daqing Oil Field, from Shenzhen’s Guomao Building to the COVID-19 “instant hospitals,” these “miracle” stories of rapid construction through total mobilization have long been rehearsed as proof of the “superiority of socialism” (shehui zhuyi zhidu de youshi) and its capacity to “concentrate resources to accomplish large undertakings” (jizhong liliang ban dashi). In the case of Huairou, the official narrative celebrated what had been achieved within “only 150 days.”

The full list was long; it included, for example, completing 40,000 square meters of new buildings, refurbishing 380,000 square meters of existing ones, upgrading 34 hotels and guesthouses, installing over 2,600 telephones and 10,000 kilometers of lines—and, finally, providing 86 tents. Meanwhile, logistical failures, such as the unfinished “Willows” and the muddy ground, were omitted or downplayed. In this framing, the political contradiction of how to contain the NGO Forum became a practical challenge to be solved through mass mobilization that involved even secondary school students (Figure 6); the state’s problem became the people’s duty, and patchwork fixes were rebranded as creativity born of limited time and resources. The tents were central to this alchemy—barely adequate substitutes for conference rooms, later praised for enabling “free, lively, and diverse discussions” and even a novel form of “tent diplomacy,” whereas their rain-induced collapses were quietly minimized.

Figure 6. Students in Huairou participating in street-beautification work in preparation for the NGO Forum, 1995. Photograph by Forrest Anderson/Getty Images.

Equally absent from official discourse was the deliberate segregation of the NGO Forum from the Chinese public. Ordinary citizens had little access to its tightly surveilled site, and its dynamic program was visible only through highly curated media coverage. Delegates recalled that whenever a march or protest approached the edge of the Forum site, guards would promptly intervene to prevent it from spilling beyond. The Forum thus became a world unto itself—visibly within China, yet deliberately detached from its public life and spaces. The lesbian tent fit seamlessly into this spatial logic, which helps explain why only Chinese-language printouts were confiscated at the tent, and why the sole Chinese woman present, later NGO organizer and filmmaker He Xiaopei, represented an exception rather than the rule. As with the Forum as a whole, the visibility of the lesbian tent was inseparable from its inaccessibility: a vivid emblem for international delegates, but carefully insulated from contact with local publics.

Not only was the FWCW sealed off from domestic China; the separation between foreign and domestic also worked in reverse, shielding international guests from contradictions within Chinese society. During the event, certain populations came under heightened control, producing an almost absurdly eclectic list: former prisoners, delinquent youth, politically disaffected individuals, beggars, non-local residents, ethnic minorities, religious groups, and people with mental or intellectual disabilities. One visible consequence of this apparatus of control was the forced dispersal of the Yuanmingyuan Artists’ Village—long viewed by local authorities as a site of artistic autonomy and political ambiguity, with symbolic ties to the legacy of 1989. Most of its artists, classified as wailai renkou (non-local residents), faced intensified harassment and eviction beginning in May 1995, under the pretext of national security surrounding the FWCW. Their removal marked not only the end of the village as a rare site of free-spirited artistic practice in post-1989 China, but also part of a broader effort to sanitize the urban landscape for global display. In this sense, the lesbian tent’s very existence at the FWCW was entangled with the silencing, displacement, and state violence that made the conference—and its carefully contained vision of progress—possible.

The government’s caution against unauthorized contact between foreign delegates and Chinese citizens helps explain the oppressive measures around the Night Woman Party, from the police surveillance to Wu Chunsheng’s later arrest (Figure 7). More than simply organizing a lesbian gathering, Wu directly challenged the state’s spatial logic of dividing foreign from domestic by arranging two busloads of international activists to a local discotheque. The party disrupted that logic in a way the lesbian march on the Forum campus did not. While the march was openly confrontational, it nonetheless remained within the bounds of managed visibility. In this sense, the Night Woman Party cannot be reduced to a momentary extension of the lesbian tent, for it crossed the very boundary that the tent, however radical, was designed to uphold.

Figure 7. Printed invite for the Night Woman Party, held on September 3, 1995. Courtesy of Wu Chunsheng and Susie Jolly.

In fact, the FWCW has long been celebrated in local queer historiography as a foundational event that facilitated lesbian community building in Beijing. Rarely asked, though, is how that facilitation took place, if the event itself remained largely inaccessible to local communities. Using the Night Woman Party as an example, I argue that its impact was not directly imposed, but was realized through local activists’ tactful, sometimes precarious, crossings of the borders of transnational spaces. Neglecting this nuance risks both rehearsing the “from-Stonewall-diffusion-fantasy” and contributing to the concealment of the Chinese state’s governing mechanism.

Back in 1995, the uneasy link between the women’s conference and the Chinese government’s agenda was already recognized. As Finnish politician and activist Hilkka Pietilä later reflected in a U.N. document, “Women all over the world were asking themselves…which would be the best way to support change in the lives of Chinese women: go there and participate in the conference in order to bring the diversity of women’s thoughts and views to the doorsteps of the Chinese, or boycott the Chinese government by staying at home?”

If the FWCW—and, within it, the lesbian tent—was shaped from the outset by the ethical dilemma of engaging an authoritarian state, then thirty years later the task is to confront the ethics of remembering. To remember the tent as infrastructure for both transnational activism and state governance does more than complicate a success story. It names a design of managed visibility: a space that concentrates transnational lesbian presence while keeping it legible to the world and illegible at home. Seeing that design has radical potentials for progressive politics: it moves beyond equating the Chinese state with a generic homophobic power and lesbians with a universal, essentially defiant subject. What then becomes possible is attention to how resistance has been—and must be—shaped by cultural, political, and spatial contingencies each community faces within a shared fight.

Such nuance is critical to the liberatory project of global lesbian activism, and it only begins with acknowledging the lesbian tent’s entanglement with state governance. This narrative resists both amnesia and romance. It reads Outright’s invitation, “See You at the Lesbian* Tent,” as: see you at the threshold, where the aesthetics of improvisation meets the muddy ground. Perhaps solidarity begins not with resolution, but in the refusal to look away.

Citation

Qiran Shang, “See You at the Lesbian Tent: Architecture and Politics of Transnational Lesbian Activism,” PLATFORM, November 10, 2025.

Notes

[1] While “lesbian” is the identity term most frequently invoked in this context—and thus throughout this article—it has long been recognized as inadequate in its inclusivity. For example, the ILIS (International Lesbian Information Service) newsletter of March 1995 noted: “The organizers [of the Lesbian Tent] realize that the word ‘lesbian’ does not encompass all women who love other women, and the mandate of the tent aims to include all women who identify in any way with these experiences.” The asterisk in Outright’s recent posts similarly signals a broader scope, extending to “bisexual, queer, trans, and intersex women, and nonbinary activists.” In Chinese communities, the commonly used term is lala, which encompasses lesbian, bisexual, and trans women.