City as Community in Zohran Mamdani’s New York

Nine weeks ago, the people of New York City elected Zohran Mamdani, a thirty-four-year-old Democratic Socialist, as its 112th mayor (give or take). Mamdani stunned the country by defeating better-known candidates, including a one-time governor, first in a landslide victory in the Democratic party primary in June and then in a decisive win on November 4, 2025. The meteoric candidacy of a first-generation Muslim South Asian born in Uganda, who grew up in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights, captured the imagination not just of the city and nation but of the world. Focusing mostly on kitchen-table issues such as the cost of housing, childcare, and transit, Mamdani energized a broad cross-section of New Yorkers, especially younger ones, by showcasing their city as one that was open, accessible, and communal.

Figure 1. View of Hudson Yards and Chelsea, Manhattan, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi, 2026.

The last time many New Yorkers felt so connected to one another was, ironically, during the depths of the pandemic, in 2020. Six feet of space and plexiglass partitions separated the city. Sheltering in place in crowded apartments, ambulance sirens rushing through empty streets, and homemade hand sanitizer and masks brought people together in solidarity. Amidst fear and anxiety, other rituals took shape: walks in parks in place of meetups at bars; family pods instead of school; and the banging of pots and pans when nurses and other essential workers changed shifts at dusk. Public space, at once dangerous and full of possibility, became redefined by everyday people who committed to stay and those who had no other choice.

Figure 2. We ACT 4 Change voter registration pamphlet, W. 100th St and Central Park West, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi, 2025.

In the five years since, rents climbed, nearing previous (pre-pandemic) peaks, while perpetually low vacancies, after a brief respite, fell to 1.41%, the lowest since 1968 (Figure 1). At the same time, gentrification resumed, particularly in Brooklyn, where historically Black neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant lost their majorities. The Mamdani campaign recognized that the challenges of living in New York center on economic precarity and quality of life issues including the environment, crime, and inflation, and it put affordability at the center of its policy proposals (Figure 2).

Mamdani’s ascendance, however, was not just about pocketbooks or policing. It was about reimagining the possibility of urban space as a generator of community and civic action (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bailey Fountain, Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. Photograph courtesy of Nasser Ahmad, 2025.

Mamdani announced his candidacy in October 2024, weeks before Donald Trump’s win in the presidential election. Shortly after, he made campaign stops in the boroughs that saw the greatest shift toward the right in the election: Queens, where he lived, and the Bronx (Figure 4). Holding a white cardboard sign that asked, “Did you Vote”? on one side, and on the other, “Let’s Talk Election,” Mamdani stood on Fordham Road and on Hillside Avenue in Jamaica, Queens. Video of the conversations became an early centerpiece of the campaign, showing voters from a variety of ethnic backgrounds speaking about life in New York. Just as important were the background tableaus of small businesses, bus and subway stops, and the all-day hustle-bustle of urban life, revealing vibrant, if somewhat run-down, neighborhoods.

Figure 4. Astoria Avenue, Queens, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi, 2025.

“Even as other candidates painted a picture of a crime-ridden and vermin-infested dystopia, Mamdani depicted New York through a cinematic lens that made it appear dynamic and alive with opportunity.”

Much has been written about how Mamdani rose from obscurity since that video and the role his social media team played. Yet even as marketing was an important tool for getting attention, the goal was always, according to the comedian Cassie Willson, to get people mobilized, “to get knocking on doors and talking to their neighbors and their community . . . . the best use [of social media] was to get people offline and into the real world.”

Figure 5. View of Hellgate Bridge, connecting Queens to Randalls and Wards Islands, Manhattan, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi, 2025.

In doing so, the campaign mobilized over a hundred thousand volunteers who, according to the campaign’s field director, canvassed in 243 neighborhoods and knocked on an astounding three million doors. What once seemed like disconnected parts of the far-flung city, divided by income, ethnicity, religion, and ideology — not to mention rivers, bays, and nearly five hundred square miles of space — were brought together by a campaign that sought to stitch the city into a whole (Figure 5).

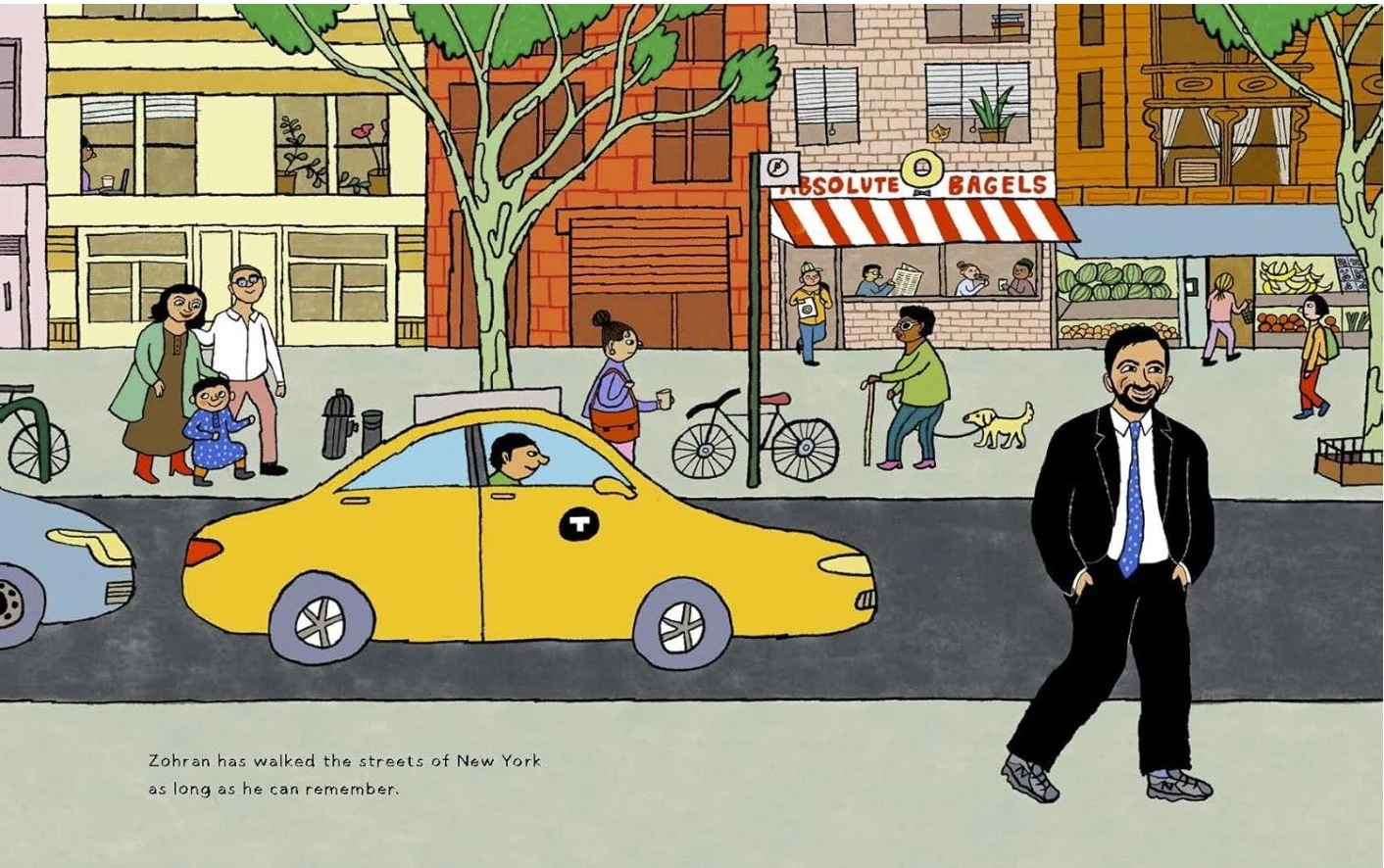

Figure 6. Cover of Millie von Platen’s children’s book, Zohran Walks New York (Penguin Random House, 2025). Courtesy of Millie von Platen.

To advance its message of accessibility, the campaign cleverly deployed the city itself. It became not just a backdrop but also a main actor, playing a central role in demonstrating its complexity and multiplicity.

Well-publicized public events shed light on different neighborhoods, from Mamdani’s Polar Bear Plunge in Coney Island on New Year’s Day to his now iconic walk across the length of Manhattan days before the Democratic primary, the city — and the idea of a unified city — served as crucial ingredients in what the campaign called “a movement.” In its characterization, New York was not just a place to survive, but to live fully and joyfully (Figure 6). From the Scavenger Hunt that mobilized hundreds across the five boroughs in August, to the Cost of Living Classic soccer tournament in October 2025, play — in a move reminiscent of mayor John Lindsay’s “fun city” sixty years earlier — became an important way to both introduce the candidate and to portray the city not as place of alienation, exploitation, and struggle but of belonging (Figure 7). Even as other candidates painted a picture of a crime-ridden and vermin-infested dystopia, Mamdani depicted New York through a cinematic lens that made it appear dynamic and alive with opportunity.

Figure 7. Page from Millie von Platen’s Zohran Walks New York (Penguin Random House, 2025). Courtesy of Millie von Platen.

In a series of video posts titled “Until it’s Done,” Mamdani highlighted New York City’s history and its central role in progressive politics, from caring for the mentally ill and dispossessed, to championing transgender and women’s rights (Figure 8). In the videos, Mamdani walks up to a desk and a chair placed outdoors, such as in a park on Roosevelt Island, on the Christopher Street Pier, on a basketball court on the Upper West Side, or on a sidewalk in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and discusses the work of mostly forgotten figures, such as gay rights activist Sylvia Rivera and street basketball star Earl Manigault, even as they themselves sometimes fell victim to poverty, neglect, or addiction.

Figure 8. Still from Until it’s Done: Nellie Bly, Zohran Mamdani for NYC YouTube Channel.

Figure 9. Vito Marcantonio, “Lucky Corner.” E. 116th and Lexington, Manhattan, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi, 2025.

Yet, as Mamdani reminds viewers, the work begun by these citizens remains incomplete. In the final episode in the series, released a day before the general election, Mamdani recounts from “Lucky Corner” (East 116th Street and Lexington Avenue) the life and work of Vito Marantonio, the socialist congressman (and protégé of Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia) who championed workers and new immigrants of all backgrounds and ethnicities (Figure 9). The segment is filmed mostly in black-and-white but the Dunkin’ sign across the street shines brightly, as do the headlights of cars passing by, depicting the bustling life of East Harlem (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Still from Until it’s Done: Vito Marcantonio, Zohran Mamdani for NYC YouTube Channel.

Figure 11. View of E. 125th Street from Metro North Station, Park Avenue, Manhattan, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi. 2025.

Urban markers, some famous and others only recognizable to neighbors, also became important parts of Mamdani’s narrative. Known to the world as the center of fashion, finance, and theater, home to elite universities and championship sports teams, Mamdani’s city was that of halal food carts, public busses, and storefront mosques (Figure 11). Indeed, it was such a mosque, the Islamic Cultural Center of the Bronx, that was the backdrop of a moving speech in the weeks before the election that ricocheted around the country and world, in which he called out Islamophobic comments made by his opponents. In a rare break from the campaign’s rhetoric of joy, Mamdani, standing in front of the modest brick façade of the mosque with mostly Black American Muslim women and men behind him, spoke of how often those that share his faith are asked to leave their religious identity “in the shadows,” as hatred of Muslims remains one of the most visible and, in the case of the mayoral elections, acceptable forms of prejudice in contemporary America (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Still from ABC Eyewitness News, October 24, 2025.

Figure 13. Poll site 118-Lorriane Hansberry, Queens, New York. Photograph courtesy of Nasser Ahmad, 2025.

The light that Mamdani’s campaign shone on city life, especially in working-class and immigrant quarters, was one that drew many voters into the public realm, not just his fellow Muslims. It included the taxi drivers with whom he had gone on hunger strike to protest predatory loan practices and the exorbitant prices of medallions; young adults who grew up in the city but couldn’t afford bus fare; and nurses and teachers whose salaries, despite their unions, are still not high enough for them to live in the neighborhoods that they work in (Figure 13).

Figure 14. El Mac in collaboration with Celso González and Roberto Biaggi of CERO Design, Puerto Rico. El Regalo Mágico (The Magic Gift), East Harlem, New York. Photograph by Kishwar Rizvi, 2025.

This image of New York went beyond exorbitant Broadway shows, high-rent office towers, and trophy apartments for non-resident off-shore investors laundering money. Mamdani presented an image of the city not as caricature or relic, but as a living, breathing entity, “for the people who build it every day.” Mamdani’s policies center on affordability and accessibility. But what really animated the campaign and his supporters was his optimistic vision of the city as a place of community and inspiration (Figure 14).

CITATION

Kishwar Rizvi, “City as Community in Zohran Mamdani’s New York,” PLATFORM, Jan. 5, 2026