Architecture Studio after the Encampments

“Abolition calls on us to be great imaginists. You have to be a big dreamer. So, use your imagination to figure out how we do this.”

--Stevie Wilson, from an interview with the author on April 14, 2024

We were three months into our first architecture studio and two months into the genocide when journalists in Gaza called for a strike. It was December 2023, and the strike was on the same day as our final review. As students, we felt unsure about what the call meant for our classroom, at a U.S. university, in this field that was still new to us. What were we making in studio? Should we stop making it?

We considered the work on our desks. Everyone was building models for the final project: a 12-inch box split into two halves. With each split based on a binary word pairing like play / study, shout / listen, or in / out, the prompt almost felt appropriate for the moment. Many of us were involved in organizing the anti-war protests on campus, and we felt split between our responsibilities there, in the growing movement for weapons divestment, and here, in our studio’s architecture coursework. The box design prompt asked us to place these conditions in opposition, then build what they made together. It was a neat idea. Yet the call to strike seemed to refuse the prompt altogether—suspend “all aspects of public life.” We looked at our boxes again.

What we learned over the next two years of our education was that putting our discomfort into boxes wasn’t enough. To realize our potential as students and people, we would have to leave the locked contradictions of a studio and its neat prompts. Only outside the studio, acting in capacities beyond design, could we grasp how architecture worked. Through the Palestine solidarity protests, we would learn how to study the structures around us, consider the contradictions they held, and practice their reconstruction. This essay recounts that process of learning.

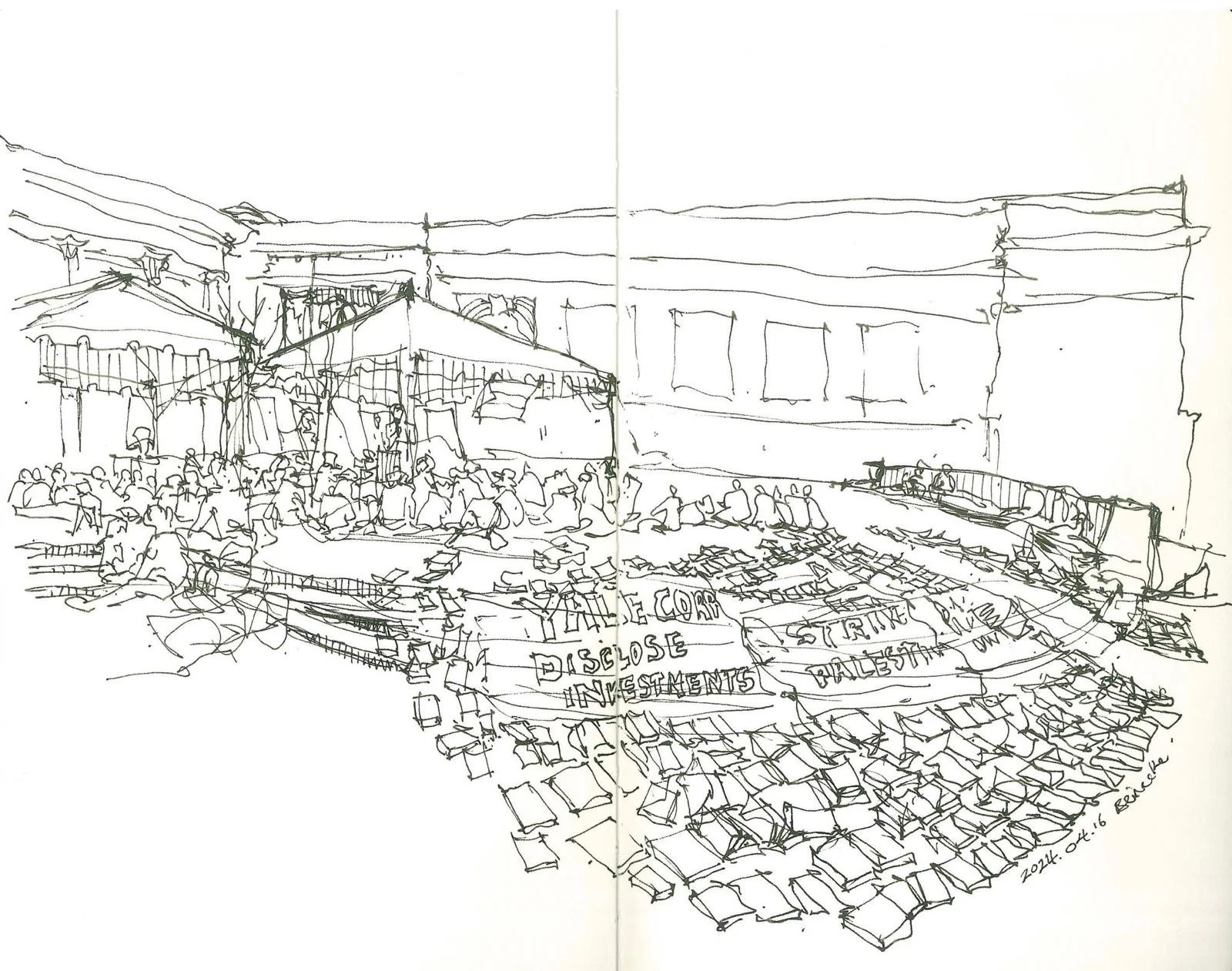

Figure 1. A sketch of the books from the first day of the protest on Beinecke Plaza. April 15, 2024. Photograph courtesy of an anonymous architecture student.

When the day of our final critique came, we didn’t strike. A few of us showed up early, passed out papers to our classmates and critics, and stood in a circle. Then, altogether, we recited a poem aloud, “A city trades prisoners, erects blockades…”

… a seven-pound box of ashes.

After many months, we still have not

scattered or buried them.

They are not him, but I kiss the box.

Naomi Shihab Nye, “For Aziz, Who Loved Jerusalem”

The review went on.

Four months after our final review, I found myself in another circle, this time outside the architecture school. It was April 2024, and we were a few days into a daytime occupation of the university plaza. With the call for “books, not bombs”, hundreds of books fanned out on the plaza steps, placed there after the university dismantled our bookshelves at the beginning of the week. Each of these days ended the same way: a singing circle before we packed up our books and posters to return the next morning (Figures 1 and 2). Tonight was cold. And after the sky drank up the last of our melodies, we sat in silence, looking down at the blank stone, our hands folded into our laps. Then someone spoke up. “Close your eyes,” she said, “and imagine this plaza full of life…”

…the books stretch to Woodbridge Hall, making the plaza colorful. People are spilling out of our space, our tents and rugs are flowing onto the rest of the plaza…people are sharing jackets, sharing food, sipping paper cups of tea. What is comforting now is not apathy and distance. It’s togetherness. And it is starting to feel like the world can be better.

I wept. It was a small group, maybe 30 people, and her words were hard to picture.

Figure 2. The books on Beinecke Plaza later in the week, just before tents went up. April 19, 2024. Photograph courtesy of Tashroom Ahsan.

I never wanted to be an architect. I became a student of architecture because those were the classrooms that felt wide open, full of moments like the one on the plaza. Teachers and peers were always pushing me to imagine things that seemed impossible. I was surprised to find a field of study that seemed resistant to cynicism, even demanded a constant envisioning of new futures. That our world could be different was a given; that we would be involved in its transformation was expected. We practiced turning paper into walls, parking lots into playgrounds. Dreams had muscle. As we watched the neighborhoods of Gaza getting flattened on our phone screens, I wondered if that muscle could make something out of our grief.

But the coincidence of the student Palestine solidarity protests with our architecture education made clear that the studio had its political limits. Studio wasn’t the place to talk about genocide, we learned. Architecture students were supposed to live in studio, and we had to be wary of anything that pulled our attention too far away from it. We might go out into the world for inspiration, snap a few pics, but then we should hurry back to our desks. The pace of the program couldn’t afford us skipping class. While our curriculum’s agnostic attitude towards the student protests was in line with the corporate university’s general aversion to risk, it felt especially wrong in architecture, the field that invited us to imagine, experiment, and build.

For architecture students, making sense of this betrayal meant reckoning with something fundamental to design education: the directive that students see themselves as problem-solvers. There is value in the problem-solving tools of design, and we needed designers for the protests, to measure out the bookshelf wall and print the paper missiles. But the protests also asked for tools that design couldn’t provide. Solidarity with a people experiencing genocide meant acting from a more degraded place, from anger and refusal. We needed things to grind to a halt, saying we would “study war no more,” if war is what study required.[1] This wasn’t new—from the start, the demand for optimistic solutions in the architecture studio had felt completely inadequate to the scale of violence many of my classmates knew in their communities. So, when the students at our campus did build something, none of us were surprised that it happened outside the studio.

Back on the plaza, the Trustees had arrived on campus. It was evening, and people stood in a circle surrounding the Maghrib prayer rugs, eyes flickering across the rows of silk covering the ground. This time when silence fell, no one needed a speech—we rushed towards each other, clinking aluminum poles and swapping the silk carpets for polyester roofs. The tents sprang up.

We sang a new song, hoping the words would come true:

Just like a tree, planted by the water,

we shall not be moved.

In their circle, the tents stood, like trees in front of a bulldozer. We thought of the over 3,000 trees uprooted or damaged by Israeli settlers during last year’s olive harvest. Inside the building next to us, our school’s police waited in riot gear, and it reminded us of the mass protests at the Gaza border fence in 2018, when Israeli soldiers opened fire on the crowds and maimed thousands of protestors. And when our curfew came, we remembered the long Palestinian resistance to intolerable conditions of life under occupation, conditions now widely recognized as genocidal. Our curfew passed and the police, miraculously, backed down. As the trucks rumbled off, we danced and sang together on the floodlit stone (Figure 3).

“No longer mediated by ID cards, pistols, or a design prompt, students and unhoused residents were free to remake a relationship of extraction into one of exchange.”

Figure 3. Students celebrate the retreat of police on the first night of the tent encampment. April 19, 2024. Photograph courtesy of Dylan Antonioli.

What lesson can be learned from the tent? Resonant with the “shanty-towns” of 1980s anti-apartheid protests, university encampments corrupt the spatial fantasy of an ivory tower, collapsing the distance between this university and those universities in Gaza which have been vaporized with this university’s money. From South Africa to New Haven to Palestine, the tents drew these connections tighter. The demand was clear: universities must divest from weapons manufacturers and suppliers. In tents, students become excess bodies collateral to the business of knowledge production, an excess mirrored and magnified one million shattered times by the wasting of Palestinian lives in the business of war. That equivalence is wrong, of course, because as students in the U.S. we are also clients, and so when universities trade on our futures, betting on our donations, it means our school is at least invested in us staying alive. The students of Gaza receive no such investment—our universities are only invested in their massacre.

The complicity of our university in the genocide of Palestinians was, and remains, something that cannot be solved by design. Design is more their tool than ours—the drones buzzing over Gaza, the settlements splitting the West Bank, the fences, the checkpoints, the guns. Genocide is design stuck in a loop, where the problem is that this land has people, has always had people. Israel, an increasingly fascist apartheid state, uses architecture as a weapon to clear people from the land and control captive populations. Watching this destruction and desecration, as architecture students we cannot limit ourselves to design thinking. If mass killing is statecraft working as normal, perhaps our task is to leave behind the elegant solutions and become a problem, too.

So, we pitched tents. We pitched tents not for some aesthetic identification with the battered tent cities of Gaza, but rather to align ourselves with the refusal of normalized state violence. This was the basis of our intimacy with Palestinians—we refused genocide; we refused the Nakba; we refused exclusive dominion over dead earth. There and here, tents are objects in motion, instruments for enacting refusals (Figure 4). While each encampment has been beautiful, none of them need to be. It is hostile architecture.

Figure 4. The encampment library, after the books had been moved into new bookshelves. April 20, 2024. Photograph courtesy of K. C.

In the end, our university proved more skilled at hostility, and the encampment got swept by police after a few days. Yet the sweep guided us towards another relationship, when we learned that an organization of unhoused people had attempted, unsuccessfully, to pitch an encampment on the city Green one month later. The Unhoused Activist Community Team, drawing multi-scalar connections between local and global dispossession on Nakba day, invited students involved in the Palestine solidarity protests to join them. They knew that many of us had experienced an encampment sweep for the first time that spring, and that it had given us a glimpse into what the unhoused members of U-ACT experienced frequently on our city’s streets (Figure 5). We accepted their invitation, and that June, students joined U-ACT for a one-night protest camp, where we distributed over 50 of the student tents to our neighbors sleeping outdoors.

Figure 5. Poster from the U-ACT encampment on New Haven Green. October 23, 2024. Photograph courtesy of Jabez Choi and the New Haven Independent.

The town-gown divide, like the distance between the U.S. and Palestine, is a fiction. University and city were never distinct, not when our university is the city’s largest employer and landowner, and not when university police patrol city streets.[2] People, money, and guns are constantly crossing our school’s borders. The histories of urban renewal, especially in New Haven, remind us that the architecture studio is not exempt.[3] We saw this porosity first-hand during the encampments, when students found themselves criminalized, racialized, and maligned as “outside agitators.” That is not to say we were made equals—police were more violent with non-students during protest arrests, for example—but rather to note how students, too, are always moments away from violating the supposedly air-tight isolation of the university campus.

Tents showed us how that porous border could be remade. Residents of the city visited our encampment not just to “agitate,” but to drop off boxes of pizza. People stayed and listened to music, sipped milky chai, and let their kids run around. Our neighbors filled the plaza with life (Figure 6). For a fleeting moment, they helped transform one bare corner of the university into public space—noisy, fractious, and open. The collaboration with U-ACT emerged from this transgression. No longer mediated by ID cards, pistols, or a design prompt, students and unhoused residents were free to remake a relationship of extraction into one of exchange. Almost 500 books from our encampment library, stamped with a note about the protests, are now housed at a drop-in center downtown (Figure 7). And when city police swept a U-ACT encampment this fall, students got arrested too.

Figure 6. People share soup at the encampment on Beinecke Plaza. April 20, 2024. Photograph courtesy of K.C.

Figure 7. Library stamp used to mark the 1500+ books from the encampment, before they were redistributed to centers and individuals across New Haven. Photograph courtesy of Ruthie Block.

As students of the built environment, might it be our responsibility to work through these holes in the fencing? Stevie Wilson thought so, speaking with me on a video call the night before our campus encampment. “Between the street and the campus…there has always been a connection,” he told me, his face lighting up my studio monitor, “so let’s rekindle that connection.”[4] Stevie is currently incarcerated in Pennsylvania. His experience with studying and organizing inside prisons is a lesson for those of us outside, that building relationships remains possible even under extreme conditions of isolation.[5] It is also an invitation—there are prisons in your state, and you can find a way to talk to the people being held in them. Following Stevie’s advice for the university, I wonder how students could reveal and reshape the cracks in the architecture classroom. What could get built if we tried harder to open our studio to the community, to multiple communities, and invited people to stay?

We have precedents for this. The Black Workshop, founded by Yale architecture students in 1968, was a student-led effort to make architectural education responsive to the needs of Black people, on- and off-campus (Figure 8). It was a support network, study group, and occasional design firm for city residents—based on a combination of university funding and Black students’ labor. As student-director Richard Dozier put it, “We want to serve the community, since therein lies our strength and the only lasting demand for our abilities.” Those students left campus to find a design education the school’s curriculum had failed to provide. In the process they reimagined the architecture school continuous with the local community, where everyone understood that “architects need not always build a building.” While the Black Workshop only lasted a few years, its memory reminds us of the political possibilities of architectural study.

“By leaving class for the plaza, we became better students in the process, learning to read the world around us on many scales…”

Figure 8. Sketch from the archives of The Black Workshop, 1969. Reproduced with permission from the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

We can also look to architectural labor organizing for guidance. Student-worker groups like the Architecture Lobby and Future Architects Front have already shown us how architecture study is inextricable from the declining labor conditions of design work. School is too expensive and too time-consuming, and our teachers are tired. In response to its crisis of legitimacy, the practice of architecture should expand, not contract—and students can help lead the way. Through testing out different types of community collaborations, students can make studio into a laboratory for the cross-industry worker solidarities that design labor urgently needs.

Studios are temporary. Today, my class graduated, and tomorrow, we will all move on from this strange world of university architecture. Some of us will go to firms, some of us will get master’s degrees. Some of us will never see a “studio” again. So, what was it worth? Maybe our teachers were right, and the only thing a studio is good for is training—whether we are training to solve problems and convince clients, or training to engage a community and organize a workplace. Maybe the answer is institutionalization, like Yale’s First Year Building Project, which emerged from a student-led effort similar to the Black Workshop and remains an enduring model of community-oriented curricula. We don’t know. The genocide in Gaza is ongoing, and unhoused people in New Haven continue to get their homes trashed in the city’s sweeps. What authority do we have to speak about the power of students, or studio, or study?

What we do know is that our studio could never survive in isolation. Faced with a learning environment already compromised by the outside world, it clarified our studies to invite more of the world in, seeing it all together. By leaving class for the plaza, we became better students in the process, learning to read the world around us at many scales, consider multiple perspectives, and prefigure, then practice, alternatives (Figure 9). It heightened our appreciation for the moments of privacy, back at our desks, that allowed us to be silent and reflect.

Figure 9. The bookshelf wall, dismantled. April 15, 2024. Photograph courtesy of K.C.

Our ongoing failure to stop a genocide shouldn’t dissuade us from trying to have ambitions beyond our own education. What this historical moment needs is more imagination, not less, and the architecture studio should remind us how to do that dreaming. Students, like all of us, have more power than they realize. They can make studio a place where that power gets practiced, where they can see what it feels like to talk with their neighbors and picture better futures together. Near the end of our call, Wilson re-emphasized the potential that students can unlock if they are willing to leave the classroom and connect with people outside. “If you’re willing to do that you will see change,” he said, “You will see growth and power, community power, collective power. That’s the role of students.”

Citation

Adam Nussbaum, “Architecture Studio after the Encampments,” PLATFORM, May 19, 2025.

Notes

[1] This is a line from “Down by the Riverside” by Nat King Cole. Historically a Black spiritual, the anti-war song became a fixture of our encampment.

[2] Incident sheet accessible through the website of Black Students for Disarmament at Yale, an organization active 2019-2022.

[3] In 1959, the New Haven city government condemned and demolished Oak Street, a community in the historically Black neighborhood, The Hill. The Route 34 Expressway built on Oak Street’s ruins was one of many postwar “urban renewal” projects that mobilized design labor, including Yale architects, to the dispossession of the city’s poorest residents. See: Brian Goldstein, “Planning’s End? Urban Renewal in New Haven, the Yale School of Art and Architecture, and the Fall of the New Deal Spatial Order,” Journal of Urban History 37, no. 3 (2011): 400–422.

[4] Interview by the author, April 14, 2024.

[5] For more lessons from incarcerated organizers, see Orisanmi Burton, Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2023). On page 175, Burton recalls a conversation with Larry “Luqmon” White in which White echoes Wilson’s call for solidarity across borders: “As [White] saw it, the strategic objective of the prison movement was to achieve ‘P + C vs. A’: Prisoners plus the Community versus the Administration, a balance of forces requiring the incarcerated to first forge solidarity among themselves and to then forge it with political communities on the outside, and in so doing, foster a shared antagonism with the state.”