The Everyday Architecture of Carnaval

Introduction

In the foreign imagination, Brazil’s Carnaval conjures images of massive samba performances pulsing with the roar of thousands of sequin-clad dancers parading through arenas to the beat of drums.

While that happens in major cities such as Rio de Janeiro, the reality of Carnaval in most of Brazil looks very different. The annual festival, arguably one of the most important elements of Brazilian identity, is commonly celebrated away from the spotlight, as a neighborhood block party. What makes the celebration at this more intimate scale equally powerful is the sister culture that accompanies it: weekly drum practices in the months leading up to Carnaval weekend in February. This article documents that culture, using photographs and drawings to catalog the everyday spaces of weekly drum practice in Belo Horizonte, a metropolitan region of six million in the Brazilian heartland.

Belo Horizonte, like every Brazilian city, encompasses two distinct zones: the formal city, of streets and property titles, and the informal city. Established in 1893, it was the first planned city in Brazil, adopting the gridded layout common to many North American cities. Beyond the center, however, is the more flexible and unplanned space of the periphery, home to the majority of the city’s rapidly growing and highly diverse population. The spaces of drum practice that I document straddle these two fabrics, reflecting physical and cultural elements of the planned center as well as the more dynamic edge.

Figure 1. Belo Horizonte, Brazil and the Serra do Curral Mountain Range, Belo Horizonte. Sketch by Lydia Collins, 2023.

Far from the glitz and glam of Carnaval itself, these spaces suggest an alternative vision for what I call “cultural architecture.” By articulating these social and physical spaces graphically in drawings (see Figures XYZ), I have transcribed social structure onto the urban fabric itself. My goal is to challenge architects’ endless quest to channel culture into particular physical forms, and to imagine new methods for conceptualizing the design of cultural space.

Viaduto Santa Tereza

Built in 1929, thirtysome years after the construction of the city, Santa Tereza bridge connects the gridded center of Belo Horizonte to the rest of the city. The underbelly of this connector hosts a constant rotation of Carnaval practices — along with rap battles, dances, political protests, skate meet-ups, and a community of the unhoused. It has been an icon of counterculture movements in Belo Horizonte for decades, and, in its openness, it provides a space for disparate communities to mix.

Figure 5. Plan and elevation of Viaduto Santa Tereza, Belo Horizonte, by Lydia Collins, 2023.

Garagem Maladeza

A private home turned bar and practice space, Garagem Maladeza sits on the border between the planned center of Belo Horizonte and the Aglomerado da Serra favela. The family that operates Garagem Maladeza has added to it in recent years, dividing the old car port into a performance area and bar that hosts weekly drum practices. They cook out of their kitchen and serve tropeiro and beer to drummers after practice, as neighbors and drummers linger. The agility of the space allows its occupants to adapt it as the group ebbs and flows throughout the year.

Figure 9. Plan and Elevation of Garagem Maladeza, Belo Horizonte, by Lydia Collins, 2023.

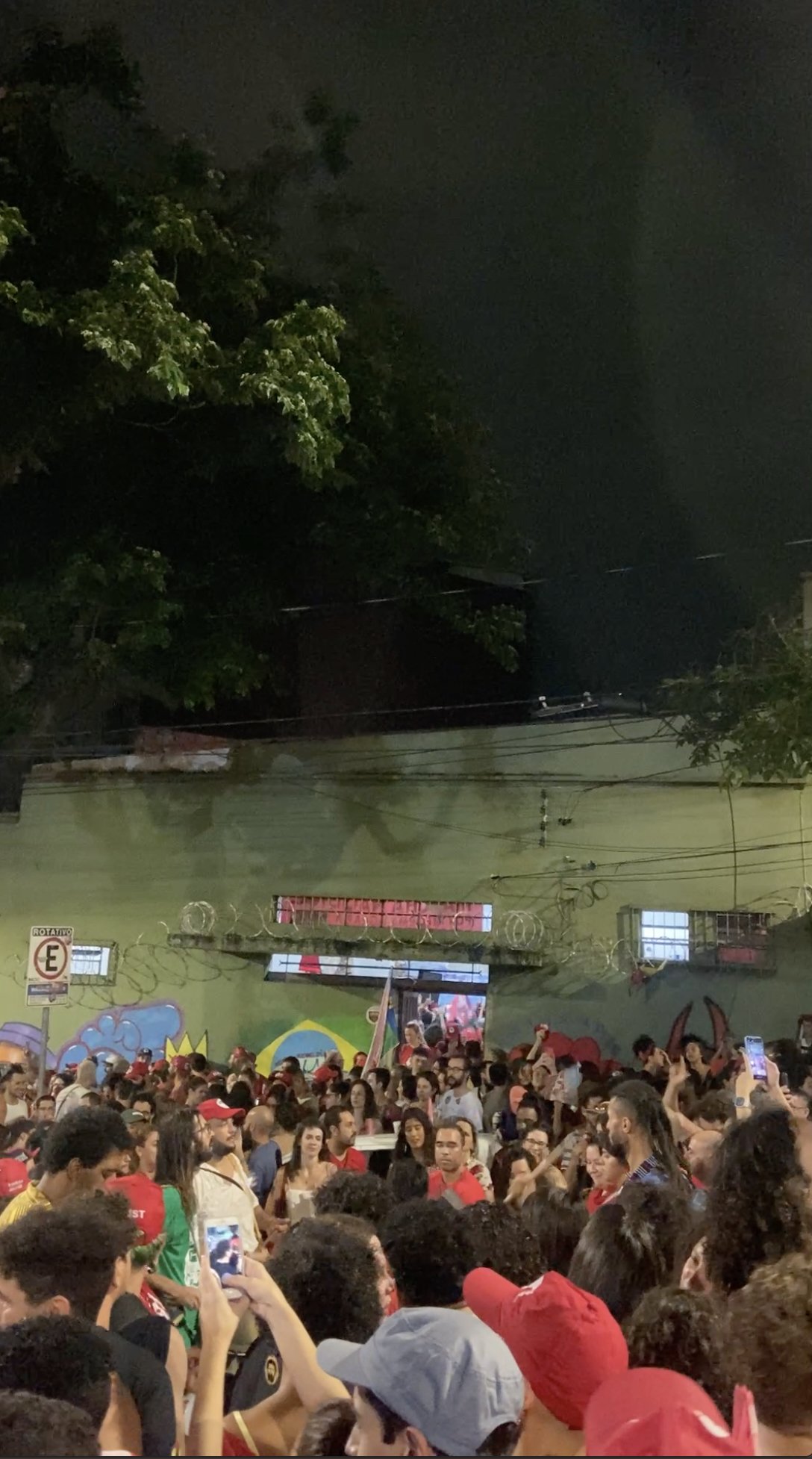

Armazém do Campo

Part grocery store, part sports bar, part samba hall, and part hub for political organizing, Armazém do Campo is a truly multidimensional building. Divided into three halls, it is also the home of Belo Horizonte’s chapter of Movimento Sem Terra (MST), a national movement for equitable distribution of land rights and sustainable agricultural practices. While the space does host a market for MST products, much of the activity that pulses through its atrium is centered around music and culture.

Figure 13. Elevation and plan of Armazem do Campo, Belo Horizonte, by Lydia Collins, 2023.

Praça Joaquim Ferreira da Luz

Until 2021, public plaza Praça Joaquim Ferreira da Luz was just another street running next to the metro tracks that divides the planned city from the periphery. Identifying a need for safe public space, neighbors worked with the city government to close the street to cars and to install planters, simple playground equipment, a painted soccer pitch, and a cement-slab stage. Multiple drumming groups practice here at night — in anticipation of Carnaval and throughout the year — providing a constant rotation of entertainment for the neighborhood.

Figure 17. Elevation and plan of the plaza, Belo Horizonte, by Lydia Collins, 2023.

Barracão de Pedro

Central in the popular music scene in Belo Horizonte is Pedro Campolina, a percussion and capoeira teacher. Campolina hosts weekly practices for various drum groups in his barracão, or patio. This space is a walled concrete slab nestled between his house and the neighbor. The bare patio has little ornamentation. On its western side is a small covered area that allows for outside practice during the rainy season, and at the southern edge there is a long bench; scattered throughout are potted plants. Students easily move instruments in and out of an adjoining storage space, and after practice there is always a group that lingers, drinking, smoking, drumming, and swinging in the hammock.

Conclusion

Across these spaces, there is a common thread. They are shells: simply adorned, fluid to movement of people in and out, malleable, permeable. They never just house one use. Their identity changes, their faces shift, their contents warp. In their simplicity, their blankness, they are legibly illegible. You know what they are hosting when they host it, but that can mutate; the space is not made for one purpose. The shedding of one skin into another is light and fluid. It happens without flare and glamour, without performance.

Figure 21. Drummers in a moment of quiet before a Carnaval performance, Belo Horizonte. Photograph by Lydia Collins, 2023.

The key to the design of cultural space that effectively straddles difference in order to rework historical divisions (such as between Belo Horizonte’s planned center and unplanned periphery) reveals itself only when the spectacle of Carnaval is decentered. When that happens, the everyday, where the city is lived, becomes apparent. This perspective shift isn’t to devalue monuments — but, rather, to observe and honor: the viaducts, corner stores, patios, and plazas that dot the city, and nurture its resilient metropolitan culture. Returning to the vernacular, the common, the side stage can guide us forward, step by step.

Citation

Lydia Collins, “The Everyday Architecture of Carnaval,” PLATFORM, Feb. 5, 2024.