Designing the Future With Children

The “future” is a topic of concern even for young children as stories about the world burning, massive floods sweeping people off of their homes and livelihoods, and countless numbers of people drowning while trying to flee into safer zones, have become the new normal on our news screens. The children see and hear about it all. They may as well be given the vocabulary to talk about what is happening around them and a sense of agency. Those working at the intersection of climate migration and children’s rights, are very well aware that “children are on the frontline.” Children are disproportionately affected by climate change and displacement. This is not to say children are passive victims of climate displacement; on the contrary, they are also among the most powerful protagonists of change and key actors in intergenerational learning. Children’s environmental leadership has been inspiring for jaded adults. Against this backdrop, the field of architecture currently has little to offer to children, considering what it actually can.

Architecture Playshop is a web-based curricular resource to teach critical literacy to young children (ages 4-9) about climate action through design. It germinated as a workshop idea in late 2019 when Haewon Shin invited me to contribute a program to the Korean Pavilion at the 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale she curated on the theme of “Future School.” When the pandemic travel restrictions were put in place, I decided to produce a modular and flexible curriculum which educators and home-schooling parents can use to teach with. A SSHRC research-creation grant in 2020 enabled me to assemble a dedicated team of students, creatives and education professionals to achieve this vision. Together with this dynamic team, I worked collaboratively, assuming the roles of creative director and art director, to develop teaching materials in an age-appropriate way.

The program’s website features teaching guides and teaching materials. It includes animations, interactive reading material, activity booklets, read-alouds on video, and a thematically organized annotated bibliography of children’s literature. The Playshop currently covers five topics: 1) building better cities 2) renewable building materials, 3) rising sea levels and their impact on cities, 4) forced migration and dignified accommodation, 5) communicating visions for the future. We got to test our curriculum in a number of educational settings and used those opportunities to improve the original material. I recount this experience of developing Architecture Playshop in the hopes it may inspire other similar projects. Through this program, we have wanted to learn from children, build their awareness about the role of architecture in climate change, and plant the seeds of future actions they can implement as adults. The effort to understand children’s perspectives is likely to create opportunities for building awareness in adults. While Architecture Playshop germinated from a workshop idea, it evolved into one which presents architecture as a worthy curricular topic in the K-6 (Kindergarten through sixth grade) setting, on par with core subjects such as science, math, or geography. Current thinking in early childhood education also supports cross-curricular problem-solving which architecture and design education can offer.

Figure 1. Artist Matt James’ illustrations (assets) for the Playshop.

“Children are disproportionately affected by climate change and displacement. This is not to say children are passive victims of climate displacement; on the contrary, they are also among the most powerful protagonists of change…”

The design, test, and the redesign of the Playshop curriculum

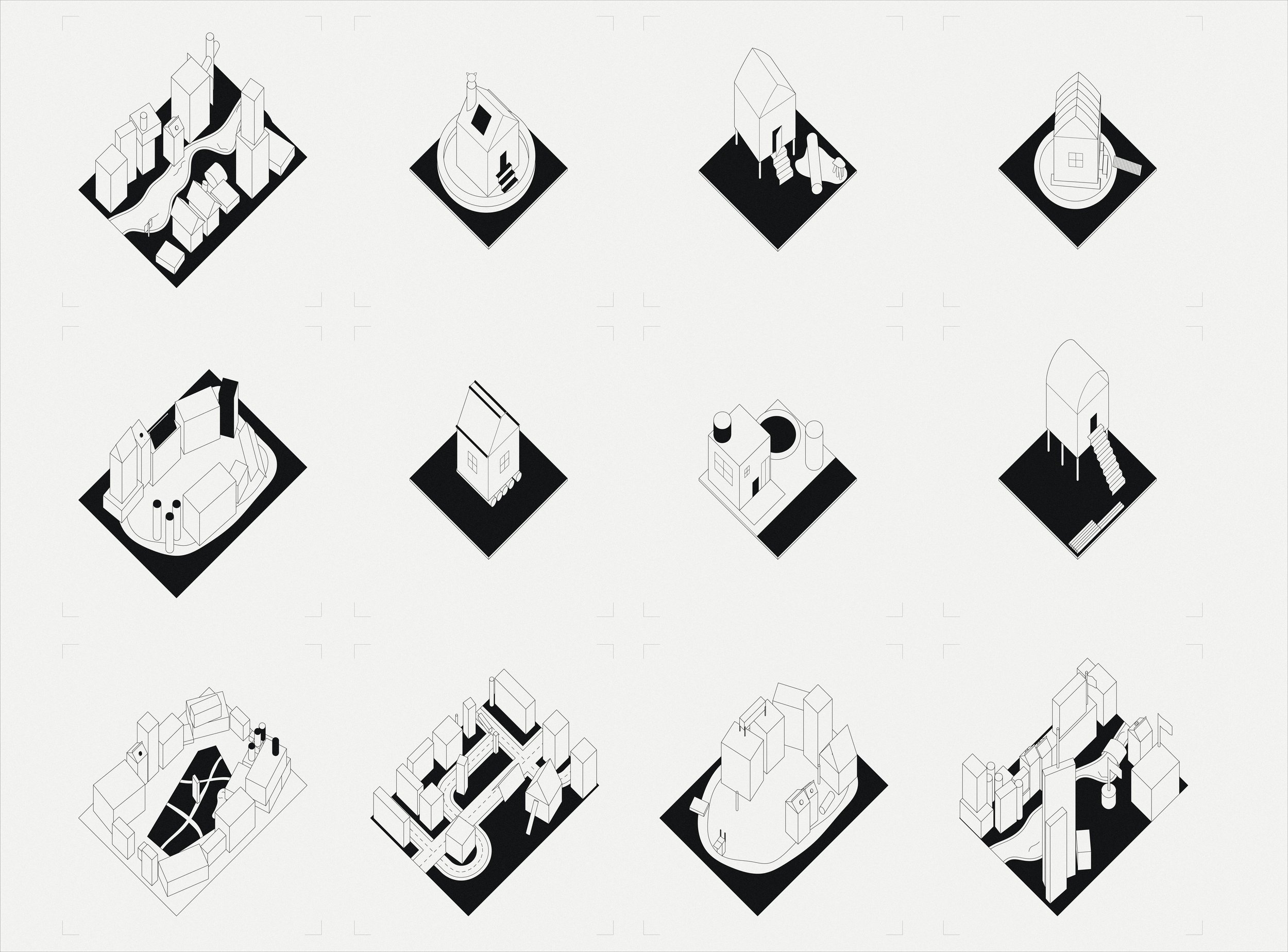

From early on we chose an artistic language that would be accessible to children yet flexible for improvement and expansion. As opposed to finished, beautiful illustrations of complete scenes, we opted for fragmented images assembled into scenes in a collage-like fashion. Matt James, an award-winning children’s book author and artist who tackles unusual subjects, e.g., rural-to-urban migration, homelessness, and death, contributed the distinct visual style of the project (Figure 1). Graphic designer Tamzyn Berman of Atelier Pastille Rose was able to assemble these fragments into scenes (Figure 2) and the animation company Happy Camper Media was able to use these fragment images, “assets,” and give life to them following a lengthy process of many team meetings (Figures 3 and 4). Our education consultant Dr. Maija-Liisa Harju wrote the teaching guides (Figure 5) and rewrote and heavily edited our narrative texts so children could easily understand the big concepts that the program introduces. Our team of undergraduate students Audrey Boutot, Sihem Attari, Zhuofan Chen created the design briefs for hands-on exercises (Figure 6) and assisted with all aspects of the project from web design to translation to filming and research for over the past three years (Figure 7).

Figure 2. A page layout using assets.

Figure 3. Still from animation using assets.

Since we piloted the project during the pandemic, going into classrooms was not permitted; our university ethics certificate allowed us only to remotely interview classroom educators. We were lucky enough to identify several different types of educational environments where volunteer educators used our material on their own and then met with us to reflect on the challenges, gains/successes, and lessons. Successful implementation occurred mostly when there was an already established relationship with the educational establishment; e.g., our first test was at the university daycare with a five year old class. We took the responses and recommendations of the educators we interviewed to heart and made alternations to the program. For example, English language presented a barrier in Quebec where the official language is French. In response, we translated our material to French at the end of the first year; and thus, we have a fully bilingual curriculum now. Print materials also presented a challenge as classrooms do not have printing capacity. In response, we developed animations from the booklets. Making the material entirely digital and web-based increased accessibility. We found out that the children absorbed the key ideas and terms, e.g., fossil fuels and their effects well. They mentioned the ideas introduced in the Playshop to parents and educators long after the workshop was completed.

Figure 4. Still from animation using assets.

Figure 5. A page from the teaching guide.

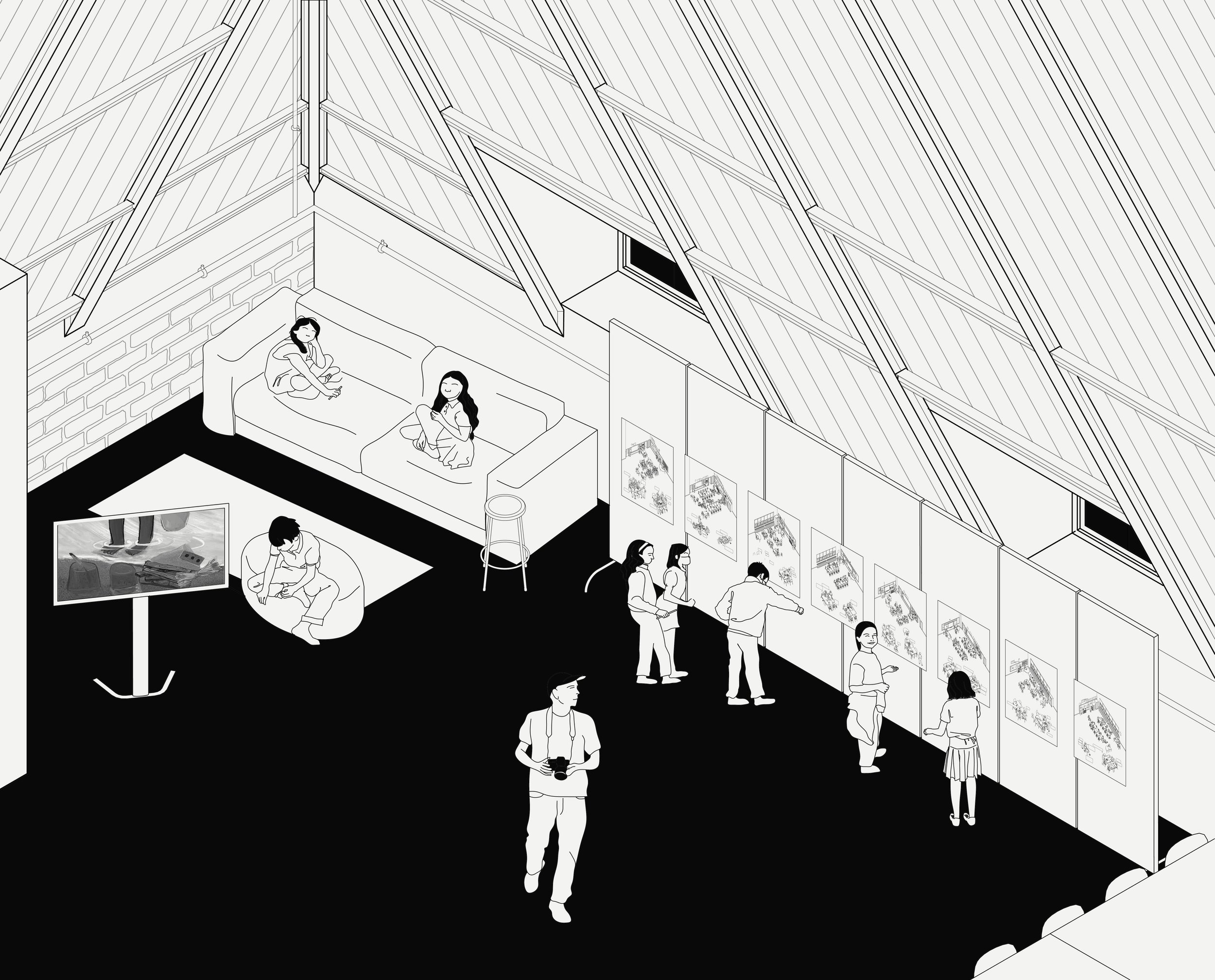

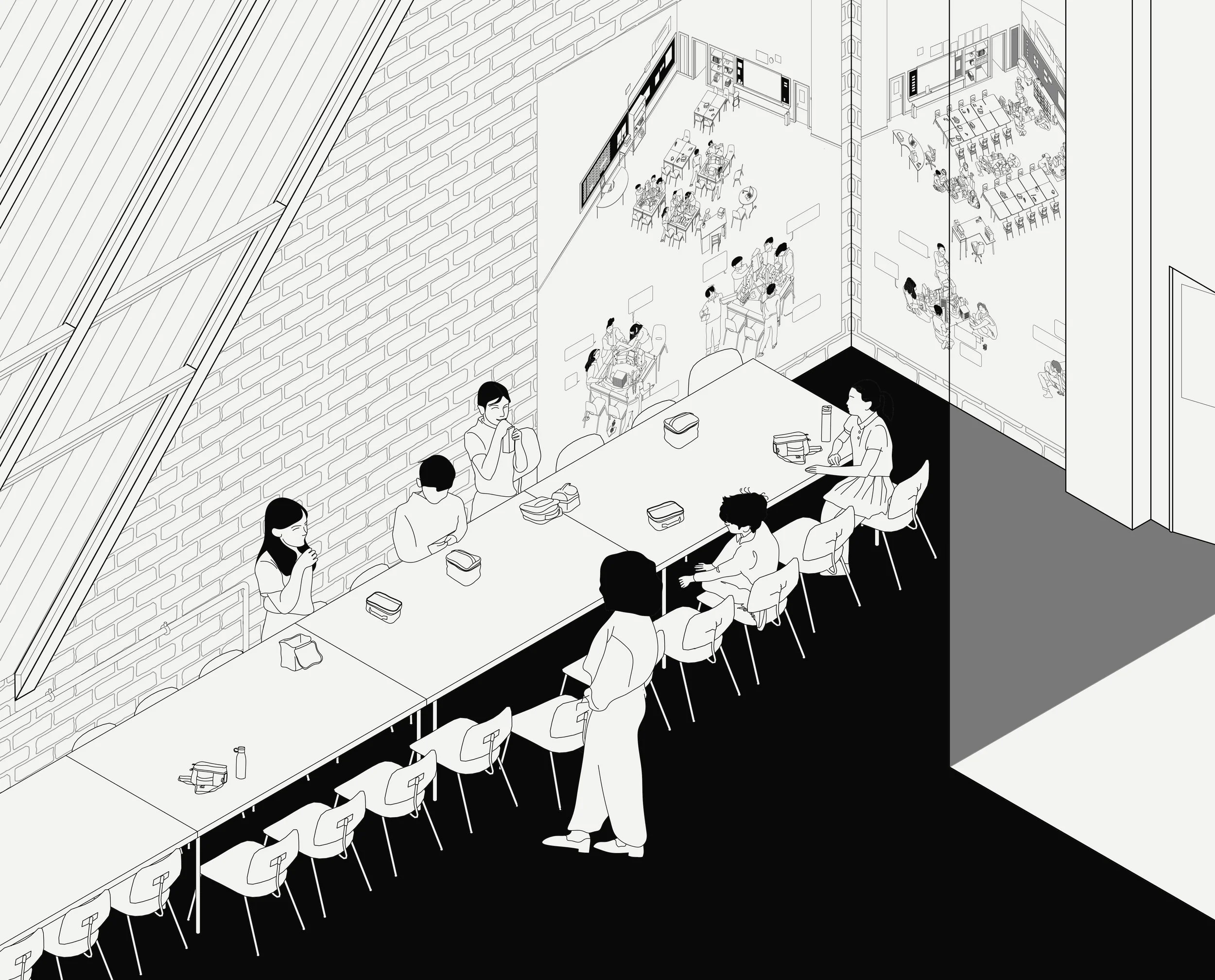

In 2022-23, as the pandemic restrictions were lifted, we approached a local school board, applied for ethics approval from the School Board, and identified the elementary school we will work with. Fourth year teachers agreed to collaborate with us. Six of our senior architecture undergraduates went into their classrooms on predetermined dates (one half day per week over five consecutive weeks) with new lesson plans adjusted to the needs and levels of fourth graders. In adjusting the lesson plans and assessment rubrics, architecture students, now referred to as “student-teachers,” broke down our session themes into the three subject areas in the 4th grade curriculum: language, science, and art. The classroom teachers did the reading part in Language; McGill student-teachers used the Science hours to talk about key scientific concepts such as fossil fuels, climate versus weather, and climate change, specific to the Playshop themes and used the Art hour to do the hands-on activities which involved making models in groups of 3-4 for different scenarios. The work culminated on the fifth week with an exhibition at the elementary school’s entrance lobby (Figures 8-10). The participating fourth grade sections proudly presented to their parents, grandparents, and other visiting classes their designs for climate action.

Figure 6. A page from hands-on activity guides.

Figure 7. Read-alouds page from the project website.

What did we learn? What did the children learn?

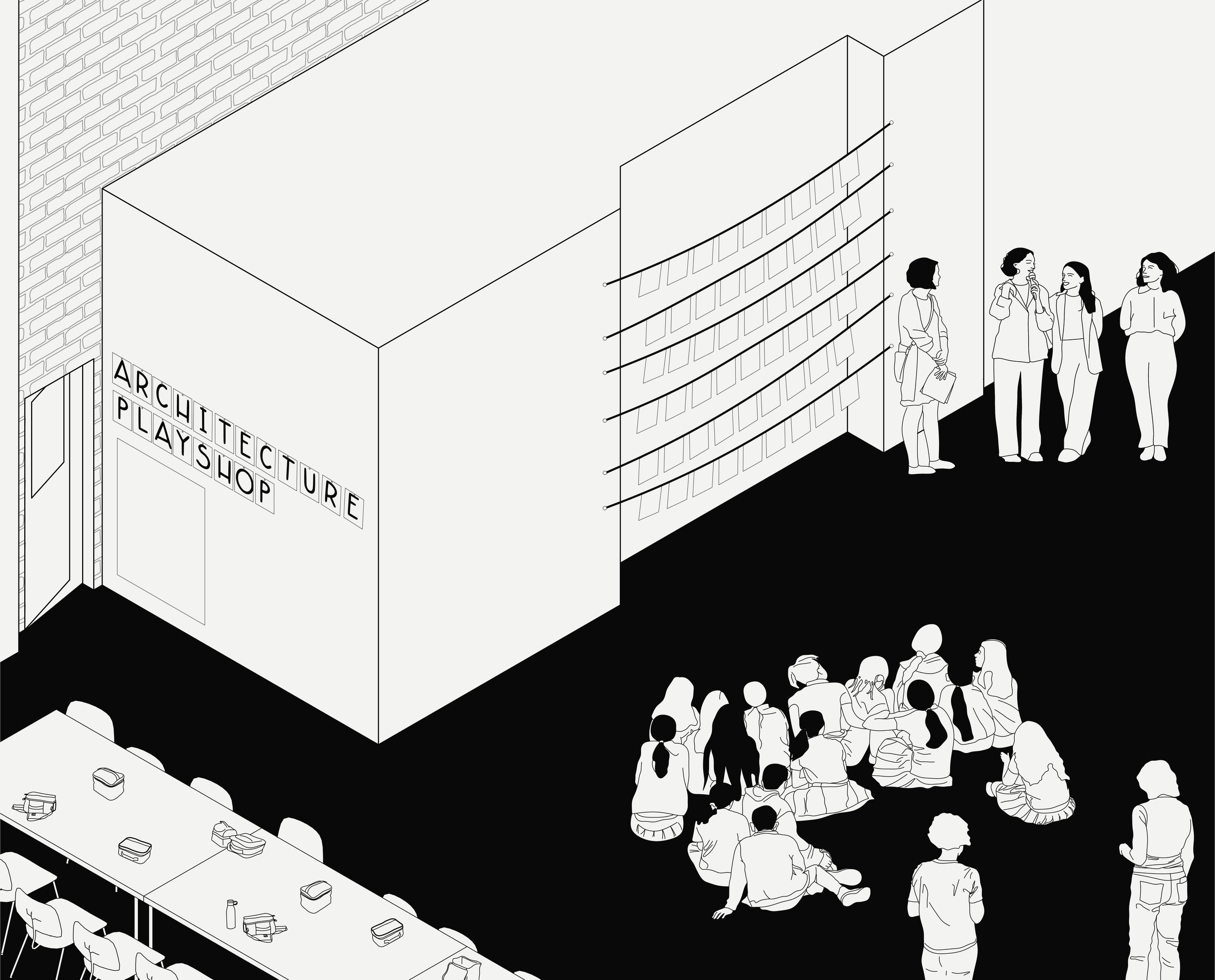

As a matter of principle, we did not take pictures of the participating children, nor did we record them using devices, because they are not our subjects; the McGill student-teachers did take pictures of the children’s output (models and drawings) and lots of handwritten notes and made sketches. At the heart of Architecture Playshop is the idea of learning from children and reciprocity. To drive this point home, we invited the children and their teachers back to the School of Architecture and campus for a second exhibition. For this second exhibition, we created original drawings of the Playshops that took place at the elementary school (Figure 11).

Figure 8. Drawing of Playshop exhibition at the elementary school in April 2023; children behind their designs ready to receive visitors.

Figure 9. Drawing of Playshop exhibition at the elementary school in April 2023; children behind their designs ready to receive the visitors.

For the visiting fourth graders to find themselves, their conversations, designs, and their build environments in these drawings was both fun and inspiring (Figure 12). Some of them stood up and spoke about their future goals. At the same event, our student-teachers (that is, McGill architecture students) remarked at how easy design was for the fourth graders and how fast they could work together to produce; they did not have the “blocks” that came to characterize, for them, the studio process. We are still processing and reflecting on how the detailed feedback from the teachers can shape future iterations of Architecture Playshop. There were, again, very practical issues to consider: for example, the elementary school building did not have storage space for the larger models the children produced during the five weeks until the final exhibition. But the messages apparently traveled well. We had positive follow-ups from involved teachers, parents, and an invitation to go back to work with the second grade. We do not expect all the concepts that were introduced in Playshop sessions to remain in the children’s memory; learning is an iterative process. Architecture Playshop will be one drop in their lifelong learning. We do expect, however, that the notion of making informed design choices as a key climate action will stick with them.

Figure 10. Drawing of Playshop exhibition at the elementary school in April 2023; children’s group photo with the student-teachers

Figure 11. Drawing of Playshop process depicted in a composite plate.

Figure 12. Students identified themselves in the drawings. Photo by McGill University Faculty of Engineering Communications Office.

In documenting the Architecture Playshop process in drawings, after the fact, we chose to use the mode of axonometric line drawings. We depicted composite classroom scenes of making and collaboration. Conversation snippets and splashes of color were added to the close-up drawings of the children’s designs (Figures 13, 14). With this mode of drawing and selective coloring, the idea is to communicate the value placed on the children’s ideas and designs without objectifying children as the focus of the drawings. Then, which moments and which conversations to choose loomed as another big question. Some of the conversations relayed to us by teachers and student-teachers showed participating students were able to discuss the many social facets of the problems introduced. For example, one student wanted to include a “House for the Rich” in the first hands-on activity to imagine a new walkable, compact, inclusive neighborhood extension to Montreal. The friends in the group suggested they should instead do a “House for the Poor” because they explained there are so many unhoused people in Montreal; the children deliberated among themselves the pros and the cons—we witnessed peer learning in action. Visualizing some of these conversations became both a representational and ethical problem. We chose to visualize conversations that show how the learning introduced by Playshop’s curricular material was translated by the children to designs. We also chose to redraw some of the children’s models and exhibited these more skilled drawings side by side with model photographs to convey the potential of children’s imagination when rendered with shared conventions that representationally clarify for adults their intentions (Figures 15-19).

“Architecture programs for children will create an audience for architecture and raise awareness about the value of design.”

Figure 13. Drawing. Detail with conversations from Playshop process depicted in a composite plate

Figure 14. Drawing of detail with conversations from Playshop process depicted in a composite plate.

Prospects

Our approach, in Architecture Playshop, has been to encourage young learners’ language and concept development concerning the role of architecture and climate action and to have them see themselves as future architects who can contribute to imaginative and sustainable design propositions in the fight against climate change. Now that Architecture Playshop has fulfilled its mandate as a research-creation project, the next stage will be to integrate the program into our teaching as a university-based service-learning course which will train architecture students to be effective communicators. Another goal of the project moving forward is to connect to and make connections among different efforts of architects and planners engaging children.[1] Such connections are meaningful and have an effect of another order and scale, larger than the sum of individual programs. While arguably not specific to Canada and Canadians, a February 2023 report by ROAC (Regulatory Organizations of Architecture in Canada) identifies that “Canadians feel disconnected from the design processes that shape their communities. They want change,” calling for a national architecture policy. Cumulatively, architecture programs for children will create an audience for architecture and raise awareness about the value of design. More importantly, they may help create engaged and empowered citizens, who are connected to the design processes that shape their communities and cities attentive to the climate emergency.

Notes

[1] The UIA Architecture & Children Work Programme runs the triennial “Golden Cube Awards” to recognize innovative program initiatives that target the youth. Architecture Playshop was Canada’s nominee for the 5th cycle of the award scheme in 2023 and received Honourable Mention in the AudioVisual Media Category in the international competition.