Charlton’s New York

On March 18, 1950, Rufus Irving Charlton passed away in Brooklyn at the age of 75. Although his name isn’t mentioned in any history of New York architecture, Charlton played an essential role in a firm that designed some of the city’s landmarks, from the Washington Square Arch to Pennsylvania Station and the Manhattan Municipal Building (Figure 1). For over forty years Charlton worked at McKim, Mead & White, the sole African American employee in a firm that employed more than seven hundred individuals between 1879 to the early 1930s. Over the course of his career, he worked his way up slowly from office boy to tracer, and from tracer to draftsman, before leaving the firm during the Great Depression. Charlton spent his entire working life in the office, and was the longest-working employee in the history of the firm.[1]

Figure 1: Waiting Room, Pennsylvania Station, New York, N.Y., 1911. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-04712.

Studies of McKim, Mead & White, or of any large firm, are traditionally told from the perspective of the owners or from architects who worked in these offices and later achieved independent careers of their own. This way of writing architectural history has skewed our understanding of the profession, especially considering that architecture firms employing large numbers of workers came to dominate practice in the United States in the late nineteenth century. It has particularly obscured how the celebrated work of well-known architects and star designers rested on the labor of individuals about whom we know very little. While such firms served as springboards to success for white, native-born, formally trained architects from privileged, Protestant backgrounds, they made progress more difficult for aspiring architects from white ethnic, working-class communities. As Charlton’s life illustrates, elite architectural firms also erected a racial job ceiling that made advancement virtually impossible for Black men.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1875, Charlton grew up in a working-class family in Fort Greene. His parents, Paul L. Charlton and Anna Eva Charlton, both worked in domestic service. His father was a native-born New Yorker while his mother moved to the city from Philadelphia. Despite their modest wages, they were able to purchase their own home on Cumberland Street, and raised a remarkable family that celebrated its achievements in the face of racial discrimination. When Paul L. Charlton died in 1927, his obituary noted that all five of his children had “attained distinction.”[2] Rufus Irving Charlton was proudly described as a “draughtsman with McKim, Mead & White.” Charlton’s brother, Melville Charlton, a graduate of the National Conservatory of Music, was a famous organist, musical director, and composer. One of his sisters, Emily C. Charlton, studied at City College and was the first Black woman in Brooklyn to become a licensed podiatrist. His other sisters, Ida J. Charlton and Florence Charlton, worked in clerical positions at the U.S. Post Office and the New York State Department of Labor. Unlike his siblings, Charlton did not go to college, or finish high school. Perhaps needing to help support his family, he left school after completing the eighth grade.

Figure 2: Low Memorial Library, Columbia University, New York, N.Y., ca. 1905. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-D4-18537.

When Charlton entered the employ of McKim, Mead & White in July, 1891, it was the most prestigious firm in New York, the go-to architectural practice for the city’s economic elite. With several large projects on the boards, it also had grown into one of the city’s largest architectural firms, with eighty-seven employees. In the early 1890s, the firm was at work on the Washington Square Arch, the campus of Columbia University, as well as the Metropolitan Club, a social club founded by J.P. Morgan (Figure 2). As the volume of commissions expanded, the partners depended on their staff of senior designers, junior designers, construction specialists, specification writers, tracers, and clerical workers to develop projects and manage the office. Most of the firm’s design talent, especially the senior draftsmen with formal architectural training from elite schools, considered their stay temporary. Even those who lacked the formal education and social connections that an architect needed to achieve independence, could rise to a position of importance in the office. Capitalizing upon the prestige of the firm, the partners made employment feel like a privilege, however. All draftsmen were forced to work for six months to a year without pay before joining the payroll. Yet even the unpaid draftsman, with the prospect for promotion ahead of them, occupied a relatively privileged position in the office.

By contrast, Charlton entered McKim, Mead & White at the bottom of the job ladder as one of the “office boys,” as the junior clerks were known who performed menial tasks. One such clerk named Charles Spelman, for example, prepared the drafting boards each morning, cut the drawing paper, and kept the drafting room clean. Charlton, meanwhile, became the firm’s receptionist. Egerton Swartwout, who worked as a senior draftsman at the firm in the 1890s, later recalled Charlton in his memoir, in which he also vividly displayed his hostility toward immigrants, Jews, and Blacks. After graduating from Yale University in 1891, Swartwout received a letter of introduction from one of Stanford White’s friends which he assumed would get him a job, despite his lack of formal training. Arriving at the office, Swartwout met, in his words, “a young colored boy I heard someone address as Rufus.” “He looked rather dubious,” he recalled, “but when he saw the engraved Century Association on the back of the envelope, he seemed more interested and called to a skinny young Irish boy…to take the letter to Mr. White.”[3] Charlton also worked as a timekeeper, keeping track of the draftsmen’s attendance and collecting their timecards at the end of the week.

“Charlton worked at McKim, Mead & White, the sole African American employee in a firm that employed more than seven hundred.”

A decade later, Charlton moved up one rung on the ladder and began working as a tracer in addition to his other duties. Drawing with ink on linen cloth, the firm’s tracers created a copy of the completed set of construction drawings produced by the junior draftsmen, which was then used to make blueprints for contractors. Although tracing required considerable skill, tracers didn’t have any creative input into their work, and thus were considered a kind of menial draftsman. According to several senior draftsmen, who looked down with contempt on the tracers, the firm primarily employed immigrants to do this work. Swartwout described the tracers as a “motley crew of foreigners,” while Harold Van B. Magonigle, another senior draftsman, referred to them as a “body of wretched beings.”[4] Nevertheless, tracing provided a rudimentary design education to many architectural workers. Charlton also made up for his lack of opportunities in the office by seeking other avenues for expression outside of it. Just as some of his colleagues were exhibiting their work at the New York Architectural League in the early 1900s, Charlton contributed to art exhibitions at the Mount Olivet Baptist Church, an influential Black congregation in Midtown (Figure 3).[5]

Figure 3. Rufus Irving Charlton, Portrait of a Woman, 1896. Image courtesy of liveauctioneers.com and Helmuth Stone Gallery.

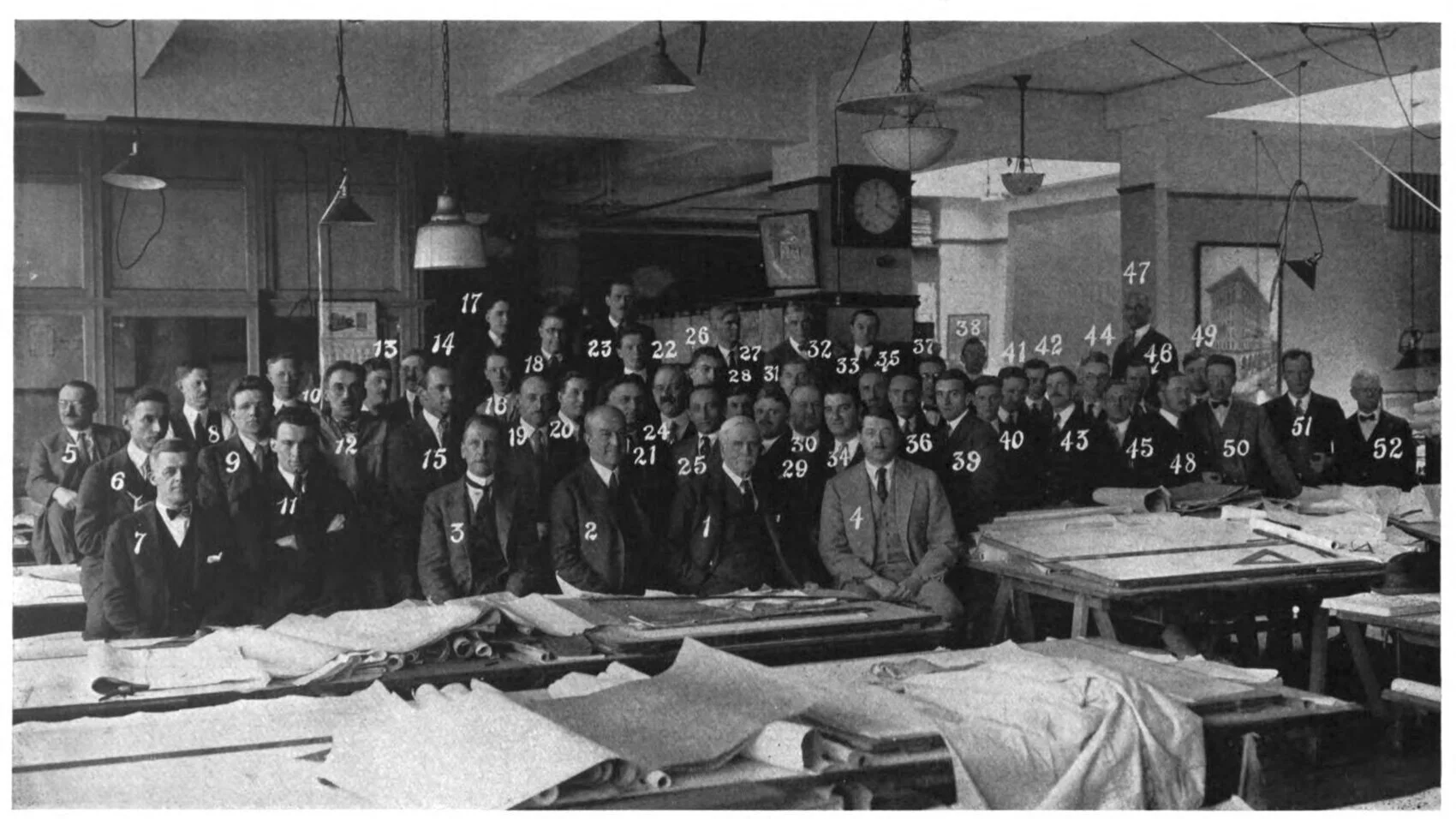

Several years later, Charlton was finally promoted to junior draftsman, meaning that he held some control over his creative work. Working from general instructions handed to them by the senior draftsmen, junior draftsmen were responsible for producing the construction drawings. In the first decade of twentieth century the firm was engaged on several major projects, including the IRT Powerhouse, Pennsylvania Station, and an addition to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, any of which Charlton may have contributed to. Despite his hard-won status, however, Charlton was still called upon at times to fulfill his earlier duties.[6] Additionally, “junior draftsman” became Charlton’s job ceiling. Over the next twenty years, the firm never promoted Charlton to senior draftsman, that is, someone in charge of projects who worked directly with clients and had authority over other employees. In 1924, when the firm published an office portrait, Charlton stood at the back. Many of the senior associates sitting around William R. Mead, the only surviving member of the original partnership, had entered the office long after Charlton started working in the firm (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Rufus Irving Charlton, identified as no. 47, shown in “The Organization of McKim, Mead & White, Architects, New York,” 1924. Pencil Points 5 (June, 1924): 72.

Charlton was one of a small number of Black New Yorkers who worked in architecture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1930, ten Black New Yorkers worked as architects, and twenty-three as draftsman, a number that included draftsmen employed in manufacturing. Many builders at the time effectively worked as architects, but the Census recorded only 128 Black builders and contractors in the city.[7] The lack of access to capital, educational inequality, and racial discrimination that prevented the flourishing of Black architects and draftsmen in New York reflected a national pattern. Between 1890 and 1930, the number of Black architects and draftsmen rose at a glacial pace, from 44 to 230.[8] Moreover, few Black New Yorkers worked in professional or white-collar jobs of any kind. While 38 percent of white, native-born New Yorkers had professional or white-collar jobs, only 8 percent of Black New Yorkers did. With notable exceptions, African Americans worked in the least desirable positions in professional, white-collar, or industrial settings and often had to struggle to keep them. “Limits on African American access to labor unions, skilled jobs, and managerial positions,” as Joe William Trotter, Jr. has explained, “reinforced their high concentration in general labor, domestic, and household service occupations.”[9]

Between the 1880s and the 1930s New York underwent a dramatic building boom which transformed it into one of the world’s largest cities. Although this boom was a powerful engine of wealth creation and social mobility for architects, builders, and building tradesmen alike, little of this wealth or opportunity was enjoyed by Black New Yorkers. With further research, we may be able to define Charlton’s contributions to the city’s architecture with greater precision, and perhaps even recover his experience in his own words. But even the little that we do know illuminates the challenges African Americans faced in a predominately white profession. For most of his life he worked in the bastion of the professional elite, but he also worked on the margins of professional life. Although firms like McKim, Mead & White were acclaimed for their paternalistic mentorship and their “esprit de corps,” Charlton had to forge his own path. This path entailed a lifetime of painstaking and poorly paid work, without reward or recognition, which makes his contribution to the building of the city all the more remarkable.

Notes

[1] “Services are Held for R.I. Charlton,” New York Amsterdam News, March 25, 1950, 15.

[2] “Paul L. Charlton, “Old Native Son of New York City, Dies,” New York Age, April 2, 1927, 10.

[3] Egerton Swartwout, “An Architectural Decade” (unpublished manuscript, circa 1930), 7-8, Walter O. Cain Papers, Avery Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York, N.Y.

[4] Edgerton Swartwout, “Working Drawings, Scale Details,” Pencil Points 2 (May, 1924): 39; H. Van Buren Magonigle, “The Preparation of Working Drawings, Part I,” The Architectural Review 16 (December, 1909): 159.

[5] “Artists at Mt. Olivet,” New York Age, November 2, 1905, 1.

[6] When the English architect, Charles Herbert Reilly, visited the office in 1909, for example, he stated that he was escorted into the reception room by a “coloured manservant.” Charles Herbert Reilly, “The Modern Renaissance in American Architecture,” Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, series 3, vol. 17 (June 25, 1910): 634. I would like to thank Horatio Joyce for pointing me to this reference.

[7] Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, vol. 4 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1933), 1130-34.

[8] Carter Godwin Woodson, The Negro Professional Man and the Community (Washington, D.C.: The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc., 1934), 33.

[9] Joe W. Trotter, Jr., Workers on Arrival: Black Labor in the Making of America (Berkley: University of California Press, 2019), 90.